The Azerbaijan–Armenia Lawfare Goes Ahead: Contrasting the Twin Judgements on Preliminary Objections within the Constellation of Inter-State Legal Proceedings

by Kei Nakajima (Associate Professor of International Law, University of Tokyo)

Published on 21 January 2025

On 12 November 2024, the International Court of Justice (‘the Court’) delivered two judgments on preliminary objections raised by Armenia and Azerbaijan in two cases, respectively, brought against each other. While the jurisdictional basis for these was the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (‘CERD’), both cases stem from the armed hostilities between the two countries and constitute part of the international lawfare launched against each other since the eruption of the Second Nagoro-Karabakh War (also known as ‘the Second Garabagh War’) in 2020, which created a situation that remained unstable until the end of 2023.

The two cases have drawn scholarly attention from the onset of the proceedings since they arguably provide another example of ‘squeezing’ any disputes into the limited compromissory clause under CERD. Nevertheless, the outcomes of these cases at the jurisdictional stage have been contrasting, insofar as the Court’s jurisdiction to entertain the applicant’s case was fully upheld in one case, while it was determined that only a limited portion of the applicant’s claims would be heard in the other.

As issue-specific contributions have already been posted elsewhere (see here, here and here), this post addresses the main thrust of the Court’s jurisdictional findings in the two cases against the backdrop of the parties’ litigation tactics and locates them within the constellation of legal actions pending before various international judicial and arbitral bodies.

Armenia v. Azerbaijan

Scepticism was directed against the genuine linkage between CERD and the case brought by Armenia against Azerbaijan (Armenia v. Azerbaijan) because the foremost concern of Armenia as listed in its first request for the indication of provisional measures involved the treatment of Armenian prisoners of war. The Court’s Order stating that it ‘does not consider that CERD plausibly requires Azerbaijan to repatriate all persons identified by Armenia as prisoners of war and civilian detainees’ reinforced that scepticism.

Nonetheless, the Court upheld its jurisdiction to entertain Armenia’s case in its entirety with a substantial majority. The main thrust of the Court’s reasoning in this respect lies in now more or less firmly established test for jurisdiction ratione materiae: asking whether acts of Azerbaijan complained of by Armenia are ‘capable of’ violating obligations under CERD (para. 94). Interestingly, the test for jurisdiction ratione materiae also had an ex-ante effect on the litigation tactics of the parties. During the oral hearings, Azerbaijan, having perceived the test as having a ‘relatively low threshold’, decided to withdraw some of its preliminary objections ‘[a]s a responsible litigant, and in the interests of the Court’s efficient conduct of this proceeding’. As a result, despite its initial impression that Armenia’s complaints were ‘entirely unrelated to racial discrimination’, Azerbaijan subsequently decided it would ‘not object to the Court’s jurisdiction ratione materiae over most of Armenia’s claims under CERD’ (para. 61).

A dissent was voiced by Judge Yusuf, according to which the majority arguably failed to examine ‘the two fundamental requirements’ for the application of CERD: whether the differentiation was based on prohibited grounds, and whether it had the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the human rights of protected persons. In the present case, however, the parties were in agreement that Armenian national or ethnic origin constituted a prohibited ground for discrimination under CERD (para. 72). Moreover, an important corollary of the ‘capable of’ test for jurisdiction ratione materiae is the deferral of a detailed assessment of facts and evidence to the merit stage (paras. 91-2), which is in line with the series of judgments on preliminary objections rendered by the Court under Judge Yusuf’s presidency (see here and here).

Azerbaijan v. Armenia

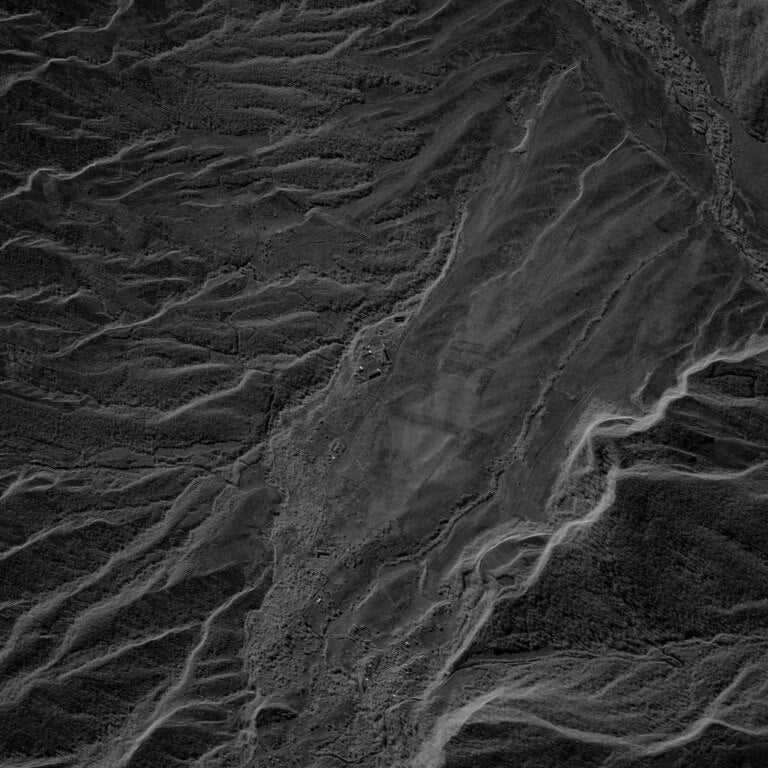

Doubts about the genuine linkage between CERD and the case brought by Azerbaijan against Armenia (Azerbaijan v. Armenia) initially arose partly due to the fact that Azerbaijan’s primary concern, as listed in its first request for the indication of provisional measures, was the removal of landmines. The Order stating that ‘the Court does not consider that CERD plausibly imposes any obligation on Armenia to take measures to enable Azerbaijan to undertake demining or to cease and desist from planting landmines’ reinforced this doubt.

This potential jurisdictional obstacle was successfully circumvented, however, by Azerbaijan’s litigation tactics, which carefully distinguished ‘submissions’ from ‘arguments’: the alleged laying of landmines was advanced not as one of its submissions but only as an argument supporting its submission regarding the campaign of ethnic cleansing allegedly conducted by Armenia (paras. 72-6). The Court’s jurisdiction ratione materiae is determined with reference to submissions rather than the arguments supporting these. As a result, it was determined that Azerbaijan’s ‘arguments’ on landmines could be taken forward to the merit stage.

The judges were split, instead, over the temporal scope of the Court’s jurisdiction and the coverage of jurisdiction ratione materiae with respect to alleged environmental harm. As to the former, the question was whether the Court has jurisdiction over acts of Armenia that occurred between 1993 and 1996, during which Armenia was a State party to CERD while Azerbaijan was not, and the thrust of the Court’s finding in this respect was a parallelism between the temporal scope of its jurisdiction and the scope of temporal application of the substantive treaty provisions between the parties concerned (paras. 44-52). The critical date was, therefore, the date on which CERD took effect between the parties as a result of Azerbaijan’s ratification in 1996, years after the end of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War, about which Azerbaijan purported to complain.

As to the alleged environmental harm, the Court concluded that none of Armenia’s conduct, even if proven, was ‘capable of’ constituting racial discrimination. According to the Court, this was partly due to Azerbaijan’s acknowledgement that the alleged degradation of forests took place ‘in pursuance of agricultural and industrial activities and a failure to mitigate wildfires’ (para. 96). Moreover, the parties were in agreement that persons of Azerbaijani national or ethnic origin were not present on the territories allegedly affected by environmental harm (para. 98). As such, the applicant’s acknowledgement and the parties’ agreement on certain facts enabled the Court, without a detailed examination of facts and evidence conceived to belong to the merits (see the joint dissenting opinion), to conclude that Armenia’s alleged conduct was neither ‘capable of’ constituting a differentiation in treatment based on a prohibited ground nor ‘capable of’ nullifying or impairing the rights of ethnic Azerbaijanis (para. 99).

The Azerbaijan-Armenia Lawfare Goes Ahead

A reading of the twin judgments might give an impression that Azerbaijan has already suffered a major defeat. However, within the constellation of legal actions currently pending between Azerbaijan and Armenia, there exists an arbitration proceeding under the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, which concerns environmental harm such as deforestation and river pollution allegedly caused by Armenia (see here). A separate inter-State arbitration brought by Azerbaijan under the Energy Charter Treaty (see here) might also be relevant, insofar as it involves hydropower and other renewable source of energy. Moreover, a number of inter-State applications lodged by Azerbaijan and Armenia against each other are currently pending before the European Court of Human Rights (see here), and the temporal scope of its jurisdiction remains to be seen. As such, claims that fell outside the scope of the Court’s jurisdiction ratione materiae may have a second chance to be heard in other international fora.

Whether either of the parties should be seen as defeated ultimately depends on the objective pursued by them. If, for instance, Azerbaijan’s litigation is aiming at ‘mirroring’ Armenia’s case for certain policy reasons, such as using the Court ‘as a platform for advertising its claims’ (see here), then the purpose of its litigation might be seen to be satisfied, insofar as its ‘argument’ on landmines may move ahead to the merit stage. Needless to say, jurisdictional determinations by the Court are without prejudice to the merit of the cases, and the need for the avoidance of prejudgment may justifiably lead to the adoption of the ‘capable of’ test, conceived as a ‘relatively low threshold’. Nevertheless, the discrepancy between the threshold for merits and preceding incidental proceedings could be exploited by parties strategically to obtain interlocutory rulings—such as judgments on preliminary objections or orders indicating provisional measures—as an independent goal. As has been the case for its jurisprudence on provisional measures, the Court’s test for determining its jurisdiction ratione materiae may also inextricably be linked with the question of whether such a use—or misuse—of the Court should be discouraged (see here).