International Law on the Silk Road:

Towards a New Methodological Paradigm

By Sergey Sayapin

Published on 6 January 2026

For several decades, international legal scholarship has been marked by a growing awareness of the limits of its canonical narratives. Critical and postcolonial approaches have exposed the Eurocentric foundations of the discipline, the structural inequalities embedded in its doctrines, and the historical silences that continue to shape its conceptual vocabulary. Yet even as scholars interrogate international law’s intellectual architecture, the field still tends to narrate its origins and evolution through a familiar Western genealogy: Westphalia, the European balance of power, positivism, colonial expansion, and the eventual universalisation of a post-1945 legal order.

This contribution proposes a different methodological orientation—International Law on the Silk Road. Rather than merely adding new historical references to an existing canon, this perspective seeks to reframe how international law is understood as a historical and normative project. The Silk Road is invoked not as a metaphor for connectivity or as an extension of contemporary geopolitical agendas but as an analytic lens that reveals international law as a genuinely cross-civilisational enterprise. It directs attention to long-standing patterns of diplomacy, trade, mobility, plural governance, and intercultural negotiation that predate the modern European state system and that continue to shape global legal ordering today. Seen from this vantage point, the Silk Road region—stretching from the Mediterranean through Central Asia to East Asia—was not peripheral to the emergence of international norms. It constituted one of the most enduring normative ecologies in world history, generating legal practices that enabled cooperation, regulated differences, and stabilised expectations across vast political and cultural spaces. Approaching international law through this lens allows us to rethink both its origins and its future possibilities.

The Silk Road as a Normative Ecology

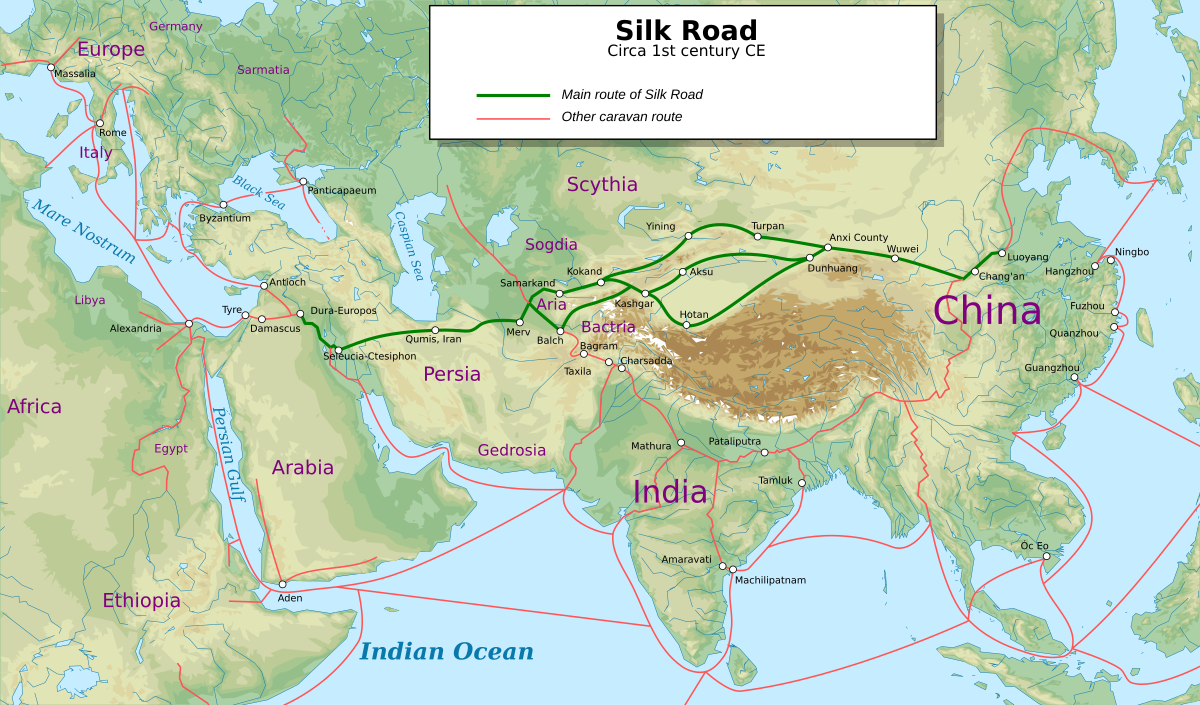

The Silk Road is commonly understood as a network of trade routes linking China, India, Central Asia, Persia, West Asia, and Europe. Yet commerce alone cannot sustain networks that endure for centuries. Movement across unfamiliar territories, interaction among culturally diverse communities, and the circulation of goods and people required normative ordering. Guarantees of safe passage, diplomatic recognition, customs arrangements, taxation practices, and mechanisms for dispute resolution were not incidental—they were deliberate legal innovations designed to manage connectivity. Across Eurasia, different political formations developed techniques of governance that established predictability across boundaries of language, religion, ecology, and political structure. The caravan routes of Central Asia, tributary systems in East Asia, Persianate practices of suzerainty, and the Ottoman Empire’s confessional pluralism all relied on negotiated authority rather than uniform sovereignty. These practices created what can be described as a pre-modern international space—a realm in which autonomy, reciprocity, protection, and layered authority existed long before the European state system crystallised. Although they did not conceive sovereignty as uniform or territorially absolute, they produced durable practices governing jurisdiction, protection, diplomacy, and mobility—practices that were not discarded with the rise of modern international law but were progressively reformulated within its emerging conceptual vocabulary.

Treating these traditions as fully fledged normative orders requires a shift in methodological stance. Rather than viewing international law as a linear European export, the Silk Road perspective understands global legal order as the cumulative outcome of interactions among diverse Eurasian civilisations. These interactions generated enduring legal concepts—plural jurisdiction, diplomatic immunity, regulation of mobility, and accommodation of difference – that remain recognisable in contemporary international law.

A Transregional Legal History

One of the persistent limitations of international legal historiography is its centre / periphery structure, which positions Europe as the primary source of legal innovation and other regions as recipients. Even critical approaches often remain tethered to this frame, evaluating non-Western regions primarily through their responses to European expansion.

The Silk Road methodology rejects this hierarchy by adopting a genuinely transregional perspective. In the framework of the suggested methodological paradigm, Eurasia is treated as a continuous normative landscape in which legal ideas travelled horizontally among multiple centres—Chinese, Indian, Turkic, Persian, Arab, and European. These exchanges were reciprocal and iterative. States and empires learned from one another, adapted doctrines through contact, and generated hybrid norms in spaces of encounter. This approach also foregrounds the diversity of political actors involved in norm creation. Empires, city-states, nomadic confederations, merchant associations, religious communities, and urban commercial hubs all contributed to the legal ordering of the Silk Road. Managing this diversity produced durable patterns of legal pluralism, which resonate with modern international law not because they share the same normative foundations but because both operate through the coordination of overlapping authorities rather than through a single, exclusive locus of sovereignty.

Continuities from Empire to Modern Statehood

A Silk Road perspective also illuminates the transition from pre-modern empire to modern statehood. Eurasian history is marked by repeated cycles of consolidation and fragmentation—from the Achaemenids and Han dynasty to the Mongol Empire, the Ottoman and Safavid states, and later Russian, Qing, and European imperial formations. These systems relied on governance techniques that balanced central authority with local autonomy, regulated transregional commerce, and accommodated religious and ethnic diversity.

Many contemporary doctrines echo these earlier practices. The protection of foreign nationals, freedom of transit, diplomatic privileges, and minority protections all have antecedents in imperial legal ordering, reflecting long-standing efforts to manage legal authority across political and cultural boundaries. Even the twentieth-century transformations of colonisation, revolution, and decolonisation did not erase these deeper structures. Newly independent states across Eurasia inherited and adapted normative legacies that continue to shape treaty practice, regional institutions, and approaches to international cooperation. The Silk Road lens thus reveals international law not as an external imposition on Eurasia but as a system shaped through long-term local practice and adaptation.

Connectivity as a Generator of Norms

Historically, the Silk Road was defined by movement. Today, Eurasia is again characterised by dense connectivity through transport corridors, energy networks, digital infrastructures, financial flows, and environmental interdependence. These forms of connectivity generate legal challenges that cannot be adequately explained through a narrow Westphalian lens. They include, for example, disputes over cross-border transit and infrastructure access, the governance of energy and digital corridors that traverse multiple jurisdictions, and environmental harms whose causes and effects are dispersed across state boundaries.

Connectivity is not merely the context of legal regulation – it is a primary generator of norms. Whenever mobility becomes central to political and economic life, law must evolve to manage risk, obligation, and expectation across borders. This logic links ancient caravan trade to contemporary regimes governing investment, transit, energy security, digital regulation, and environmental protection. The legal frameworks governing today’s Eurasian corridors reintroduce layered authority, negotiated governance, and plural regulatory traditions. Understanding these developments requires a methodology attuned to historical precedents of managing connectivity across difference.

Towards a Silk Road Methodology

The core contribution of International Law on the Silk Road is methodological. It proposes a reorientation of how international lawyers research, interpret, and teach the field by questioning the assumptions that continue to shape its historical imagination and analytic habits. Rather than treating international law as a system with a singular point of origin and a linear trajectory, this approach understands it as a product of sustained interaction across regions, cultures, and political formations.

First, the Silk Road methodology insists on historical depth. In this sense, international law did not begin with the Peace of Westphalia, nor with the nineteenth century’s ‘standard of civilisation’, even though the contemporary state-centred system of international law—grounded in sovereignty, territoriality, and institutions such as the United Nations—emerged much later. While these moments remain important for understanding the modern European state system, they capture only a fragment of the normative practices that have governed relations across vast parts of the world. A genuinely global discipline must therefore take seriously earlier and non-European traditions of legal ordering that structured diplomacy, commerce, conflict, and coexistence across Eurasia for centuries. This does not entail romanticising pre-modern arrangements or ignoring the violence and hierarchy embedded within them. Rather, it involves recognising that many contemporary international legal concepts—such as negotiated authority, plural jurisdiction, protected mobility, and the management of difference—emerged from long-standing practices of transcontinental interaction rather than from a single civilisational source.

Second, the Silk Road methodology requires cross-civilisational analysis. Legal traditions are not self-contained or internally homogeneous systems—they are relational formations shaped by contact, exchange, and contestation. The Silk Road perspective therefore traces how legal ideas travelled across political and cultural boundaries, how they were adapted to new contexts, and how hybrid norms emerged in spaces of encounter. This approach moves beyond both diffusionist models, which portray law as spreading from a single centre, and reactionary models, which define non-European legal development primarily in terms of resistance. Instead, it emphasises reciprocity, mutual learning, and the co-production of norms across multiple centres of authority.

Third, the methodology foregrounds connectivity as an analytic category. Movement—of people, goods, capital, ideas, and institutions—is not a peripheral phenomenon but a structuring force in legal development. The regulation of mobility has always generated normative responses, from caravan protection and diplomatic immunity to contemporary regimes governing trade, investment, energy, and digital infrastructure. By placing connectivity at the centre of analysis, the Silk Road approach reveals how international law emerges from practical needs, evolves through repeated interaction, and accommodates pluralism across space and time.

Taken together, these methodological commitments shift international legal scholarship away from singular origins and static categories toward interconnected trajectories and dynamic processes. They invite a more nuanced understanding of international law as a historically layered, transregional, and relational enterprise – one that is better equipped to engage with the complexities of a genuinely multipolar world.

Why This Perspective Matters Today

The contemporary international legal order faces profound uncertainty. Multilateral institutions are strained, geopolitical rivalry is intensifying, and cooperation on climate change, migration, and public health remains fragile. At the same time, new forms of regionalism and transnational infrastructure are reshaping global governance. In this context, a Silk Road methodology is not antiquarian. It offers conceptual tools for understanding overlapping legal regimes, hybrid institutional arrangements, and normative pluralism in a multipolar world. Such situations arise, for example, in the governance of transnational infrastructure corridors that combine domestic regulation, bilateral agreements, and multilateral standards, or in regional economic and security arrangements that operate alongside—and sometimes in tension with—global treaty regimes. Above all, it reminds us that international law has never been the product of a single civilisation but the outcome of sustained interaction among many. By re-examining Eurasian legal histories and foregrounding connectivity as a driver of norm creation, International Law on the Silk Road invites a reorientation of the discipline—one that is historically grounded, methodologically plural, and genuinely global.

Dr Sergey Sayapin is Professor of Law at KIMEP University (Almaty, Kazakhstan) and Distinguished Visiting Global Scholar at the NUS Centre for International Law (2025). The author acknowledges with thanks the helpful comments provided by Dr Ntina Tzouvala on an earlier draft.