A first look at the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework: What’s in it for Indo-Pacific participants, and can it succeed?

(Part 2)

By Celine Lange

Published on 10 November 2022

Part 2 of the blog series on the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), launched in May 2022 by President Biden, examines the possible benefits of the Framework for its Indo-Pacific participants, as well as its potential implementation difficulties. It is argued that the IPEF may not have much to offer economically to most of its Indo-Pacific participants, and that its regional impact could remain limited, owing to the IPEF’s opt-in structure, the relative shallowness of its commitments, and the lack of an enforcement mechanism.

I. IPEF’S DUBIOUS BENEFITS FOR THE INDO-PACIFIC COUNTRIES

The US’ interest in re-engaging, for geostrategic reasons, with the Indo-Pacific is obvious. IPEF participants’ appetite to get involved in detailed negotiations will, however, likely vary depending on each State’s individual situation and, in particular, whether it already has an economic partnership with the US or is a CPTPP party.

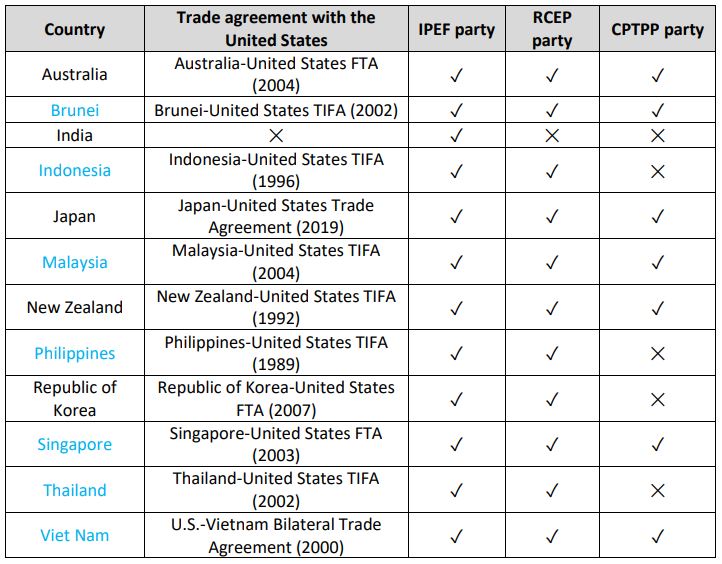

In this respect, it bears noting that, as the US are not expected to join the CPTPP, future IPEF agreements will be the only channel to engage with the US for some of the IPEF signatories. Moreover, for the IPEF countries that already have economic agreements with the US, the nature of these agreements—from simple Trade and Investment Framework Agreements (TIFAs) to full-fledged Free Trade Agreements—will be another significant variable influencing the Framework’s attractiveness for each participant. These differences are outlined in the table below.

Table 1: IPEF signatories’ economic agreements with the US

ASEAN countries are in blue

Three categories of IPEF countries can thus be identified.

-

- For countries already having an economic partnership with the US interest in the Framework could remain limited. Two possible counterarguments may nevertheless be made:

– IPEF provisions could act as a modernising add-on to older treaties which do not include, for instance, sustainable development or labour commitments (e.g., Australia-United States FTA (2004)).

– Some countries have not signed full-fledged trade agreements with the US but rather mere TIFAs, which tend to be short and much narrower in scope (focusing on trade and investment) and could thus use extra substance along the lines of IPEF’s proposals.

- For countries already having an economic partnership with the US interest in the Framework could remain limited. Two possible counterarguments may nevertheless be made:

These two counterarguments are however weak, given the many uncertainties hanging over the exact content of any future IPEF negotiations (a point further developed in this post below).

-

- For CPTPP parties, IPEF presents an opportunity for the US to re-engage with its former TPP partners in Asia (Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Viet Nam). Yet, these countries are already well-equipped regionally as members of one or two mega-regional trade agreements (CPTPP and RCEP), with CPTPP in particular giving access to a trading space going well beyond Asia and reaching to Canada, Chile, Mexico, and Peru.

- For India, entering into an economic partnership with the US for the first time, the prospective benefits of the IPEF theoretically seem more equally shared than for countries in the previous groups.

However, India’s decision not to sign on Pillar I discussions after the first Ministerial meeting in September 2022, because of concerns on possible labour commitments in particular, is not a very encouraging signal for the other countries in this group. It is difficult to imagine how India could re-join the discussions in these circumstances despite the declarations of its Commerce Minister.

II. CHALLENGES IMPLEMENTING THE IPEF

In addition to the potentially limited trade value of the IPEF for most of the Indo-Pacific participants, the Framework’s design and structure could cause implementation difficulties. Four types of implementation challenges can be identified, which are briefly examined in turn below.

Following-up

Before the IPEF’s broad contours can become firm commitments, agreements need to be concluded between participants. There is currently no certainty about the US’ capacity to durably engage with the thirteen IPEF countries or the partners’ interest in the long term. While the negotiation objectives announced in September 2022 demonstrate participants’ willingness to move quickly and to elaborate on the Framework’s content, ‘the more concrete phase of work’ lies ahead.

The Framework’s vagueness was an advantage at the pre-signature stage to get all thirteen participants onboard. However, this might be problematic to scope out each IPEF pillar. The Framework could indeed remain an empty shell if only a few IPEF countries achieve successful negotiations. The IPEF could also be regarded as an unfair partnership as its language suggests that more substantial undertakings are expected from Indo-Pacific participants than the US. Coupled with the variable levels of motivation mentioned previously, negotiations can thus be expected to be difficult or protracted.

‘Picking and choosing’

The IPEF is based on a flexible mechanism allowing signatories to choose to participate in certain parts of the Framework. Discussions on certain pillars, or components thereof, will probably be particularly laborious (e.g., on Pillar IV which entails important reforms). Some IPEF countries might thus choose to stay away from the more onerous commitments completely and favour easier undertakings instead, potentially leaving entire parts of the Framework unexecuted.

Another possible undermining factor could be signatories’ fear of being at a disadvantage vis-à-vis their IPEF partners if they choose to commit to provisions which require costly domestic reforms and with no guarantee of similar commitments undertaken by other participants. Concerns on a probable asymmetry in undertakings might result in a ‘wait and see’ approach.

Incentivising enforcement

Although the Framework does not provide for enforcement mechanisms, IPEF countries, according to US officials, would hold up their end of the bargain in order to receive the incentives offered by the agreements. What precisely these ‘incentives’ will entail, however, remains unclear, especially given the absence of tariff adjustments.

A further incentive to implement the Framework’s commitments would be for IPEF participants to attract ‘business from American companies’. While this could be the case for countries like Viet Nam and Indonesia that do not have trade agreements with the US, incentivising investment by American companies overseas does not tie up well with the general anti-liberalisation climate currently prevailing within the US.

Furthermore, these ‘carrots’, envisaged as enforcement incentives, do not come with any ‘stick’, i.e., a dispute settlement mechanism or any other kind of remedies. The absence of such a feature, which would be critical to ensure that undertakings among IPEF’s participants are enforced, stands out even more in the context of modern trade agreements, which typically include dispute settlement mechanisms, or provide for internal dispute procedures pursuant to which complaints can be received and handled by mandated offices on both sides.

US Congress voting

A final potential hurdle to mention pertains to domestic support for the IPEF inside the US. Responding on whether IPEF agreements would go to Congress at some point, US Trade Representative’s sibylline remark was: ‘Congress needs to be a part of shaping what we do with our partners’. While efforts have been made to distance the IPEF from traditional trade agreements and to show how it would benefit American workers, there is no guarantee that domestic constraints would allow the agreements to get through a Congress vote without witnessing a repeat of the TPP’s unceremonious epilogue.

III. CONCLUSION

US leaders are confident that IPEF participants are willing to work closely with the US, and that its members have now ‘laid a strong foundation for fruitful collaboration to come’, but respective engagement levels could vary greatly. Furthermore, the Framework’s opt-in feature might turn out to be the IPEF’s Achille’s heel, even if US officials commented that India’s withdrawal from Pillar I discussions was the very demonstration of IPEF’s built-in agility. This is in addition to several other critical obstacles potentially standing in the negotiators’ way, notably, possible concerns about asymmetries in undertakings, in particular for developing countries.

Given the TTP’s history, IPEF participants know that it does not get any better than this for the moment. Yet, it will arguably take more for the US to remain credible as a trading partner in the region. Their hosting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum in 2023 will be an occasion of a progress stocktaking on IPEF-related negotiations. The US will also need to address concerns about the IPEF’s longevity, as the prospect of another Trump Administration in 2024 could potentially spell the Framework’s death.

The author would like to thank Research Associate Professor N. Jansen Calamita and Dr Charalampos Giannakopoulos for their guidance and constructive comments on the blog posts.

Read Part 1 of Celine Lange’s IPEF series here.

Read Part 3 of Celine Lange’s IPEF series here.