The ICJ’s 2023 Judgment in Nicaragua v Colombia:

A New Chapter in the Identification of Customary International Law?

By Ori Pomson

Published on 28 July 2023

Introduction

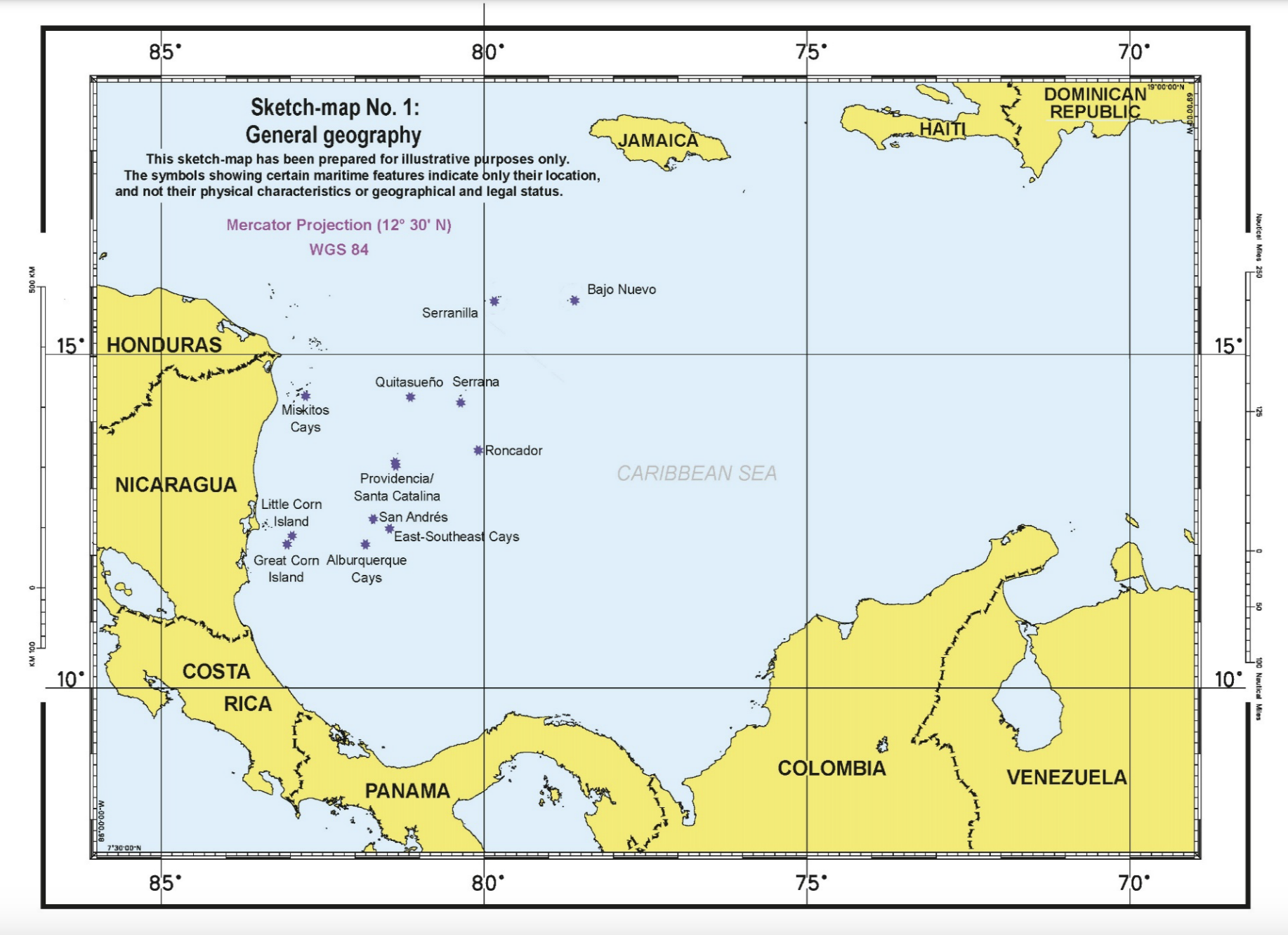

On 13 July 2023, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) rendered its judgment on the merits of the case concerning Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 nautical miles from the Nicaraguan Coast. The Court decided that Nicaragua was not entitled to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles (nm) from its baselines (an “outer” or “extended” continental shelf) which fell within Colombia’s entitlement to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and continental shelf within 200 nm from its baselines.

From a law of the sea perspective, the judgment is significant since the ICJ addressed for the first time whether a state’s entitlement to an outer continental shelf may overlap with another state’s entitlement to maritime zones within 200 nm. However, the most significant aspect of the judgment was the Court’s reasoning in reaching its conclusion on the state of customary international law relating to the continental shelf.

This post will first provide some background on the judgment. It will then summarise its main findings as well as individual opinions appended thereto, with an emphasis on the question of identifying customary international law. It will subsequently offer some observations before concluding.

Background

In 2013, Nicaragua instituted proceedings against Colombia, requesting the ICJ to delimit its claimed outer continental shelf entitlement with Colombia’s maritime entitlements. Subsequently, in 2016 the ICJ concluded that Nicaragua’s principal submissions fall within its jurisdiction and were admissible. However, before proceeding to hear the parties’ oral arguments on the merits, the Court decided for the first time in its history—seemingly to Nicaragua’s frustration—to bifurcate the proceedings on the merits. The Court considered ‘it necessary to decide on certain questions of law’ before potentially addressing complex technical and scientific questions. The Court thus directed the parties to address ‘exclusively’ two legal questions. The first question, on which the case finally turned, asked:

Under customary international law, may a State’s entitlement to a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of its territorial sea is measured extend within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State?

The Judgment of 13 July 2023

The Court approached this first question from two perspectives. First, it examined ‘the relationship between the régime governing the exclusive economic zone and that governing the continental shelf’, and then it addressed ‘certain considerations relevant to the régime governing the extended continental shelf’ (para 68).

On the first issue, the Court emphasised that ‘the legal régimes governing the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf of the coastal State within 200 nautical miles from its baselines are interrelated’ (para 70). In this regard, the Court quoted at length from its Libya/Malta judgment, where it stated that, ‘[a]lthough there can be a continental shelf where there is no exclusive economic zone, there cannot be an exclusive economic zone without a corresponding continental shelf’.

The Court then addressed considerations relating to the régime governing the outer continental shelf. The Court made three points. First, under customary international law, the bases for entitlement to a continental shelf within and beyond 200 nm differ: while entitlement to a continental shelf within 200 nm is solely based on distance from the coast, entitlement to an outer continental shelf depends on whether the continental shelf is a natural prolongation of the state’s territory (para 75). Second, the aim of the substantive and procedural conditions under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) for establishing an outer continental shelf ‘was to avoid undue encroachment on the sea-bed and ocean floor and the subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, considered the “common heritage of mankind”’ (para 76). Hence, it may be assumed that states considered that an outer continental shelf could only extend into areas outside the jurisdiction of any other state.

Perhaps most significant and controversial was the Court’s third point (para 77). The Court observed that ‘the vast majority’ of UNCLOS states parties which made submissions to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS)—the body which makes ‘final and binding’ recommendations for states claiming an outer continental shelf (UNCLOS Article 76(8))—refrained from asserting entitlement to a continental shelf within 200 nm of other states’ coasts. The Court considered that this practice ‘is indicative of opinio juris, even if such practice may have been motivated in part by considerations other than a sense of legal obligation’. Additionally, the Court was unaware of any state not party to UNCLOS claiming an outer continental shelf encroaching upon another state’s 200 nm maritime entitlements. The Court thus concluded:

Taken as a whole, the practice of States may be considered sufficiently widespread and uniform for the purpose of the identification of customary international law. In addition, given its extent over a long period of time, this State practice may be seen as an expression of opinio juris, which is a constitutive element of customary international law. Indeed, this element may be demonstrated “by induction based on the analysis of a sufficiently extensive and convincing practice” [quoting from Gulf of Maine].

The Court also emphasised that its reasoning ‘is premised on the relationship between, on the one hand, the extended continental shelf of a State and, on the other hand, the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, within 200 nautical miles from the baselines of another State’ (para 78). For the said reasons, the Court answered the above-quoted question negatively (para 79). Accordingly, Nicaragua’s submissions for delimitation could not be upheld, since they were premised on the assumption that its claimed entitlement to an outer continental shelf could encroach upon Colombia’s maritime entitlements within 200 nm from its coasts (paras 86, 91, 99).

Individual Opinions

Most of the judgment’s operative paragraphs were decided by 13 votes to 4. The four dissenting voices were those of Judges Tomka, Robinson and Charlesworth and Judge ad hoc Skotnikov, each of whom appended a dissenting opinion. Judge Nolte joined the dissenters in voting against one of the operative paragraphs concerning a somewhat minor point, opining that despite the Court’s principal legal conclusion it should have determined for the parties whether certain Colombian islands—according to Nicaragua incapable of sustaining human habitation or economic life—were entitled to an EEZ and continental shelf. Judge Xue appended a separate opinion, taking issue with the Court’s legal conclusions; nevertheless, she voted with the majority in rejecting Nicaragua’s submissions, seemingly unconvinced by Nicaragua’s case on the facts. Additionally, Judge Iwasawa appended a separate opinion supplementing the majority’s reasoning, while Judge Bhandari appended a declaration criticising certain terminology employed by the majority. For reasons of space, I will only address in further detail how several of the individual judges addressed the question of identifying opinio juris.

Judges Tomka, Xue, Robinson and Skotnikov considered it problematic to infer opinio juris from the abstention of states from claiming an entitlement to an outer continental shelf which encroaches upon another state’s entitlements within 200 nm from its baselines, highlighting the existence of alternative explanations for such abstention. Such explanations were put forward most elaborately by Judge Tomka (para 53; citations omitted):

(a) [T]o put off a diplomatic row; (b) to avoid the objection procedure of the CLCS, which would result in blocking or seriously delaying the consideration of its submission; or (c) because a given area may not be worth claiming.

Regarding reason (b), it should be noted that under the CLCS’s Rules of Procedure, the CLCS will not consider submissions where a dispute between states exists regarding the establishment of outer limits, unless all parties to the dispute consent to the CLCS’s consideration.

Conversely, Judge Iwasawa elaborated on the majority’s approach in identifying custom. In particular, he made the following point:

States usually do not curtail themselves when they believe that they have a right. If an issue is regulated by international law and States abstain from certain conduct in a way that is inconsistent with their own interests, it may be presumed that their abstention is motivated by a sense of legal obligation.

Observations

The identification of opinio juris is fraught with uncertainty. States often refrain from stating outright that ‘under customary international law the rule is X’. For example, in the Truman Proclamation, which marked the beginning of the development of customary international governing the continental shelf, there is not a single mention of custom or international law.

While there are no legal rules which determine the confidence one must have in classifying a pronouncement or act as reflecting opinio juris, states and judicial bodies alike must determine the applicable law in a given situation. For a legal advisor, the most straightforward solution is to communicate the uncertainty to whom they are advising, who will in turn need to consider the risks deriving from the uncertainty when deciding how to act. Yet, a judicial body in contentious proceedings, unless prepared to engage in the heresy of pronouncing a non liquet, must determine whether or not the relevant precedents of state practice are accompanied by the necessary opinio juris in order to decide on the existence or inexistence of rules of customary international law.

As a question of law, there is no burden or standard of proof applicable to establishing the existence of opinio juris of a given state. However, in a different context when tasked with determining a question of law—namely, in determining whether it has jurisdiction—the ICJ adopts a preponderance standard, examining whether the ‘the force of the arguments militating in favour of jurisdiction is preponderant’. In the absence of other proposed tests and given both instances concern a state’s acceptance of a legal rule or arrangement, the preponderance standard also seems appropriate for identifying whether a particular state has, in fact, expressed opinio juris on a given matter.

Assuming a preponderance standard is applicable, the Court’s inference of opinio juris in the present case is questionable. While it may be fair to assume that a legal obligation constitutes a red line in a state’s everyday decisions, policy considerations play an important role for states in deciding how to act within their rights (cf Jurisdictional Immunities, para 55). Thus, contrary to Judge Iwasawa’s suggestion, states often refrain from exercising their rights to the fullest. The reasons Judge Tomka and others put forward for doubting the existence of opinio juris are pertinent examples for reasons why a state would refrain from exercising its rights to their fullest, and I would argue that they are preponderant in the present case. Yet, given the context in which the law governing entitlement to an outer continental shelf developed—which is presented in the judgment almost like a prelude to the Court’s inference of opinio juris—it is entirely within the realm of reasonableness to perceive things differently.

Conclusion

Some may argue that the Court’s approach in Nicaragua v Colombia to inferring opinio juris marks a shift from past decisions. However, it remains to be seen whether the judgment signifies a change in the ICJ’s approach to identifying customary international law, or whether the circumstances of entitlement to an outer continental shelf will allow the Court to distinguish the present judgment. To the extent the judgment came down to the degree of confidence in potential evidence of opinio juris, the present judgment leaves much wiggle room.