Symposium: Small States, Legal Argument, and International Disputes

A collective answer: Small States, sea-level rise and the interpretation of UNCLOS

by Frances Anggadi

Published on 19 July 2023

Many eyes are on Vanuatu, which is leading global efforts to seek an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the obligations of States in respect of climate change. The recent UN General Assembly resolution sets in motion the ICJ’s usual procedures for dealing with such a request. Perhaps less visible, but equally seeking to influence the global conversation on the legal dimensions of climate change, there are two overlapping groups of (predominantly) small States which have made clear their views on the preservation of their maritime zones notwithstanding sea-level rise.

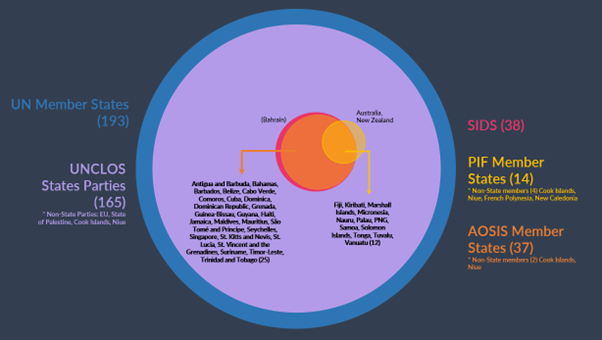

The first of these is the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), which in August 2021 issued the Declaration on Preserving Maritime Zones in the Face of Climate Change-related Sea-Level Rise. The second is the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), whose leaders issued a similar declaration the following month. Combined, the PIF and AOSIS represent 39 UN Member States, all of whom are party to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (see Figure 1, below). Notably, excluding only Australia and New Zealand, the remainder of PIF and AOSIS members are also Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

Why has this concentration of small States taken this course of action? What would success look like, and what would be necessary to achieve it? This post will offer some brief responses.

Since around 1990 (Caron), many scholars have asked whether sea-level rise will result in the loss or diminution of maritime zones (eg International Law Association’s Baselines Committee). The issue arises because under international law of the sea, as maritime zones flow from land territory, the rules specify how and where to establish maritime zones depending on particular features of the land. For example, a baseline for a maritime zone may be established by reference to the low-water line of a feature that is above water at all times, or the seaward edge of an island’s fringing reef (but not from low-tide elevations located at a distance from the coast). But what happens to such a baseline if the low-water line recedes as a result of sea-level rise, or if the extent of the fringing reef is reduced not only by sea-level rise but ocean warming and acidification? These questions relate to the respective fates of the land—impacted by climate change effects—and the maritime entitlements it supports: are their fates necessarily intertwined? Climate change was not contemplated at the time UNCLOS was concluded, but many scholars consider that the likely legal answer is that maritime zones could shrink or even disappear if coastlines recede, and perhaps whole islands submerge. This is commonly described as an ‘ambulatory theory’ of baselines or maritime zones.

As scholars continued to raise such concerns, regional declarations in the Pacific since 2010 affirmed the importance of preserving maritime jurisdictional rights (Anggadi). But the 2021 declarations by the PIF and AOSIS have two distinctive features. Firstly, the declarations make a clear interpretative claim about UNCLOS. The preservation of maritime zones is not framed as a future aspiration, or to be (only) politically desirable, but as a present legal claim on the basis of the ‘principles of legal stability, security, certainty and predictability that underpin the Convention and the relevance of these principles to the interpretation and application of the Convention in the context of sea-level rise and climate change’. Secondly, it follows that such a claim is ‘universal’ in nature, in the sense that it purports to have implications for all UNCLOS Parties, and perhaps general customary international law.

These two features recall key elements of the legal statecraft of small States in the context of international dispute settlement (Guilfoyle): a small State may adopt a legal rather than political framing of the issue in dispute, as well as seeking to ‘internationalise’ the issue, rather than casting it as a local or bilateral matter. Both impulses may similarly be seen in the approach of the PIF and AOSIS in framing their position on the preservation of maritime zones as an interpretative claim about UNCLOS, a treaty with a very wide membership.

But at first blush, a claim for the legal stability of maritime zones appears at odds with the widely-held view of many scholars that baselines are generally ambulatory. However, framing such a claim as an interpretation of UNCLOS invokes the analytical framework of treaty interpretation, calling attention to the potential legal influence of State practice (as ‘subsequent practice’) and States’ views (evidencing interpretative ‘agreement’) (Article 31(3)(b), Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties). The success of this approach rests on the strength of evidence for making out these two elements of treaty interpretation. Assessing such evidence in April 2022, the International Law Association’s Sea-Level Rise Committee considered that at that stage the requirements of Article 31(3)(b) had not been made out. One year later—with the benefit of further debate at the UN General Assembly’s 77th session—it is arguable that a stronger case exists in support for the PIF and AOSIS position. For example, some States have recently expressly supported the legal positions in the declarations (eg Germany, Japan), and the United States has also stated it will not challenge baselines and maritime zones that have been established and not updated in light of sea-level rise. No State has made any explicit protest, though some States remain cautious (eg United Kingdom).

At this stage, it appears that there is a reasonable likelihood that the strategy pursued by the PIF and AOSIS to preserve their maritime zones in the face of sea-level rise will succeed. And if so, because the means to pursue this objective is framed as a universal interpretative claim about UNCLOS, it has significance not only for the small States at the forefront of discussions, but also for all UNCLOS Parties and potentially for non-Parties too. The collective action behind the Vanuatu ICJ initiative has succeeded so far in bringing a request for an advisory opinion to the world court. To the question of whether UNCLOS permits the preservation of maritime zones notwithstanding sea-level rise, the actions of PIF and AOSIS have offered a collective answer: with the increasing acceptance of the international community, this, too, looks likely to succeed.