Delimitation and the Human Regard:

Notes on Dr. Suedi’s study on Man, Land and Sea: Local Populations in Territorial and Maritime Disputes before the International Court of Justice

by María Teresa Infante Caffi

Published on 4 October 2023

A thought-provoking study

The thoughtful reflection that Dr. Suedi proposes is an invitation to look at a silent side of territorial and maritime delimitation, not less of judgments of international tribunals especially the International Court of Justice (ICJ or the Court). The study explores the interlinkages between terrestrial or maritime delimitations and their human dimensions. The question about how and to what extent State litigants’ concerns for the impact of maritime disputes or territorial disputes on their local populations are factored into the Court’s decision-making process is the main purpose of this article. Through this, the role of equity, either potential or current, is extensively discussed.

Exploring in the various hypotheses of this study, a first question relates to the maritime delimitation process which represents a fair part of the ICJ case law. In general, this process can be showcased in isolation from any non-physical geographical element, as solely dependent on the possession of the coastal territory concerned. Besides, there is also the approach that it is admissible to consider other elements and factors in the reasoning and deciding on delimitation. It is evident that this matter concerns both the methodology and the result of the process.

As Dr. Suedi’s study illustrates, delimitation always involves a sovereign fibre altogether with economic, social, political, and even cultural interests and rights of the population or populations. Thence, one of the questions that maritime delimitation raises is the factual and legal weight to give to these activities, both private ones or related to States’ actions (legislation, surveillance, search and rescue, authorizations) in the assessment of an existing maritime boundary or in the drawing of such a boundary. The analysis goes further and assumes that equity is inherent in the legal delimitation process, making equitable considerations addressing the needs of local populations part of the legal methodology as well, and not contrary to it.

Thus, a first hypothesis comes out and this is that equity is the very content of the applicable rules. This assumption may be contrasted with the reference to the Gulf of Maine where the Court would assert that ‘for the purposes of such a delimitation operation as is here required, international law, as will be shown below, does no more than lay down in general that equitable criteria are to be applied, criteria which are not spelled out but which are essentially to be determined in relation to what may be properly called the geographical features of the area.’ And, the Court would continue to say that it had, ‘on the basis of these criteria envisaged the drawing of a delimitation line, that it may and should—still in conformity with a rule of law—bring in other criteria which may also be taken into account in order to be sure of reaching an equitable result.’

Jan Mayen is one of the cases in which the ICJ has delved further into factors other than geographical to uphold the validity of the rule of law in such terms that it would say that ‘the attribution of maritime areas to the territory of a State, which, by its nature, is destined to be permanent, is a legal process based solely on the possession by the territory concerned of a coastline.’ Furthermore, the Court would highlight that there was no reason ‘to consider either the limited nature of the population of Jan Mayen or socio-economic factors as circumstances to be taken into account.’ Here, the arguments addressed the question of the weight to give to the relative economic and population weight in the relevant territories.

In general terms, these judgments must be analysed in the light of the value and meaning of the key provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) regarding delimitation of the territorial sea (Article 15), the exclusive economic zone (EEZ, see Article 74(1)) or continental shelf (Article 84(1)). In the last two provisions, the delimitation is to ‘be effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution.’ The goal of predictability of this process is not described in detail in the hermetic provisions applicable to the EEZ and the continental shelf.

The reference ‘to achieve an equitable result’ will then depend on each negotiation or judgment. In that regard, the author would like to add a degree of flexibility in this argumentative exercise by giving a higher weight to elements other than physical geography and possible existing maritime boundaries determined at precolonial times. The question is the level and intention in which flexibility should be introduced according to the applicable law of the case and its characteristics. Here, the question raises the point of asserting first whether there is an agreement in place, as a main task mandated by UNCLOS provisions.

Doctrines and needs

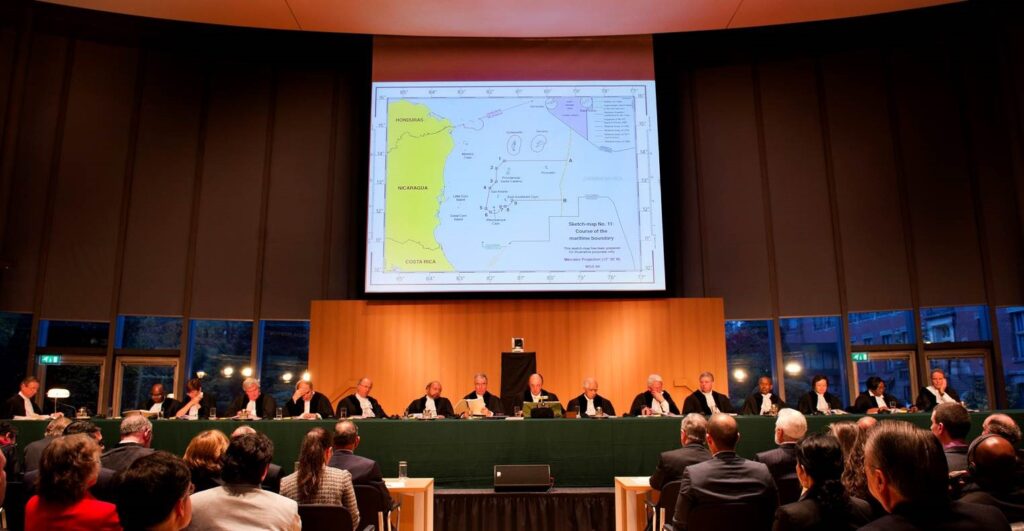

On another set of subjects, a doctrine that plays in the direction of pre-existing legal arrangements that may have a bearing on the territorial or maritime delimitation, the concept of uti possidetis juris has been discussed with different results. This rule has occasionally encountered difficulties, when contrasted with an effective possession ground which relies on persistent practice, or geographical features poorly delineated. In this respect, it is to be noted that the doctrine has been less controverted and even directly upheld in Hispanic America as compared to cases in other regions. Whenever, according to the Court’s views, the evidence regarding the content of the uti possidetis juris rule in a particular situation has been found insufficient, although not defied as a possible valid title, the effective control by a government over a population has come to illuminate issues of attachment of a territory to the sovereign power of a party. In the Territorial and Maritime Dispute between Nicaragua and Honduras in the Caribbean Sea, the ICJ decided that the principle was not applicable to the maritime delimitation in that case, recalling that the 1906 Arbitral Award ‘which indeed was based on the uti possidetis juris principle’, did not deal with the maritime delimitation.

The Court stretched the role of this principle in the Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Dispute, where title to sections of the land boundary based on the uti possidetis juris principle posed the question of their location while adjoining other sections based on agreed lines. There was also the issue of the presence of persons of one nationality on the frontier zone of the other party, which entails complications arising from the fact that nationals of one of the parties may have been exercising traditional activities on the other side of an alleged frontier, or when those persons may have acquired private rights (property) on the alleged territory of the other country. Cases such as Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Dispute or Kasikili/Sedudu Island illustrate the exhortative way in which tribunals may deal with this sensitive matter, including the plea for the concept of due regard to the needs of the parties, used in Burkina Faso/Niger.

On a close subject, in Burkina Faso/Mali the Court decided upon the division of a frontier pool (Soum), where the boundary had not been object of an indication by either party. The Court, that had set out that ‘[e]quity does not necessarily imply equality’, would soften the argument with the assertion that ‘where there are no special circumstances the latter is generally the best expression of the former.’ This prevalent approach is a confirmation that equity is to be applied as a derivation of justice, infra legem, which is not derogated by the UNCLOS provisions on maritime delimitation.

It is also worth recalling that in the Burkina Faso/Niger dispute, the Court noted that ‘the requirement concerning access to water resources of all the people living in the riparian villages is better met by a frontier situated in the river than on one bank or the other.’ This seems to indicate a particular sensitivity towards the population needs, the same that arouse in respect of nomadic or seme-nomadic populations. In those cases, the issue of an effective presence of a party’s power over the territory and a population, was not deemed to play against the doctrine but to address gaps in the applicable rules and/or to support a formula that facilitated their application to the circumstances of a case.

On a central theme of the article, one may wonder to what extent the concept of equity—even to remedy a post-colonial situation—can operate separate from an existing agreement—essential to so many frontiers—that reflects the will of the parties. Here, a test not only of justice but also of legitimacy can be introduced. The author postulates the idea that catastrophic consequences are to be avoided by courts and that it can be done through the discretion in the use of equity, as an attribution of the Court. An attractive assertion in terms of the language, and whose merits deserve a thorough analysis. The question appeals to pose a different view, that is, that the discretion granted to use equity by law in each case might not be employed to contribute to the possibility of achieving catastrophic consequences. In that sense, the South West Africa Cases provides basis to think about the validity of existing law not as opposed to equity, but on the contrary, to envisage that law is directly connected to humanitarian grounds and goals. Thus, the limited scope attributed by the Court to the applicable legal set of norms in that case, missed the opportunity to enhance the place and role of humanitarian elements as part of the existing law, not only as a moral ideal.

In maritime delimitation cases, when introducing the question as to what an equitable result is and which are the methods to achieve it, this article exhibits an enormous potential for discussion. Courts and tribunals have confronted this subject either through the fisheries activities or the presence of exploration and extractive mineral activities on the seabed with a particular importance in a country’s economy. The article recalls that these matters may be present in a disputed zone through various arguments pointing out to the pre-existence of a boundary, the value of historic rights or the inclusion of those actions under a relevant circumstances concept to adjust a provisional delimitation line during a delimitation.

Fishing and resource-oriented activities

Considering these categories, the article refers to judicial cases where fisheries have been either mentioned or invoked to explain or confirm a decision. It is a fact that parties have referred to fisheries activities when pleading before the Court as a basis to enhance an argument or to confirm the reasonableness of a certain preferred line to conduct economic or conservation activities. As rightly noted in the article, fisheries have been central in disputes such as in Jan Mayen, or related to territorial and maritime controversies, such as in the Territorial and Maritime Dispute between Nicaragua and Honduras in the Caribbean Sea, and in Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v Colombia). The exercise of a regulatory power in respect of fishing activities has been extensively present in these cases. There were also other resources in the area in Jan Mayen.

The selection of cases shows a variety of examples that are indicative of a special interest in introducing the resources argument and the dependence or straight connection between the population and those sources of economic and even survival activities. From a methodological perspective, the Gulf of Maine illustrates one of the possible approaches to the delimitation process conducted by an international tribunal. Whereas the parties emphasized the weight of fishing activities, the Court explained its task as one primarily based in law where geographical features were determinant factors, and then those activities could be noticed in view of the overall result.

Another perspective is that courts seek to judge guided by the stability principle (and even legal value) applicable to boundaries, together with other considerations based on the exclusive application of law without consideration for non-juridical elements which could entail risks for the objectivity of the process. The plea that ‘the existence of the principle of equity stands as evidence that legal formalism is not absolute and the co-existence between the law and other considerations is feasible’ is provocative, if not challenging.

In this respect, it seems appropriate to raise the question, among other reasons, as to how States will submit controversies to courts and tribunals if they know that equity/separate considerations are not to be assessed according to law, in particular when parties rely on agreements in force which have already been negotiated taking into consideration interests, geography, and other motives. This is not mere legal formalism, it is also a way to enhance the role of negotiations and agreements, where opposing views find an accommodation. A different situation—which does not defy the legal validity of an agreement—is the one where equity can be introduced infra legem according to legal parameters in both, maritime or territorial delimitation. And this without having recourse to the ex aequo et bono method or a contra legem exercise.

Regarding maritime delimitation, the case-law spans from the formulae employed in Maritime Dispute (Peru v Chile), where an existing boundary was admitted extending up to 80 nautical miles, continuing with a new line defined as if it were and equidistant line from selected points, to the application of a standard to be used in making an adjustment to the provisional equidistance line to ‘allow the coasts of the Parties to produce their effects in terms of maritime entitlements in a reasonable and mutually balanced way’, as set out in Maritime Delimitation in the Indian Ocean (Somalia v Kenya), to avoid potential cut-offs. These cases reflect less a test of the equitableness of a decision but rather the appreciation of the relevant circumstances to weigh a provisional line based on geographical factors, as a central element in the delimitation exercise, and as seen from the judicial own understanding of the law.

To conclude these comments, a word about Peru v Chile: it was not about fisheries and the dependence of the populations of one party from marine resources versus the other country, but about the validity as a frontier agreement of a set of treaties adopted over time, since 1952 and their application in terms of authority and enforcement activities. The respective entitlement of each party was then, not dependent on the respective fishing activities, although fisheries are present in the local and national economy of both countries. Another perspective posed by the ICJ judgment is that the extension of the agreed maritime boundary up to 80 nautical miles, along the parallel of latitude by a tacit agreement, and as an inference from the practice. The 200 nautical miles doctrine that originated significant changes in the law of the sea institutions was to some extent revisited by this decision. Thus, the construction of a provisional equidistance line would commence at the endpoint of that extension.