Symposium: High Politics at the International Court of Justice

High Politics and the

International Court of Justice

By Gleider Hernández

Published on 17 October 2024

The notion of ‘high politics’ in international adjudication is only paradoxical if one insists strictly on a conceptual separation between law and politics. Though the point of law and legal systems is to transcend politics, or at the very least, to organise law and legal institutions around processes that operate independently from brute politics, only the most strident formalist would maintain that law is entirely separate from politics. To my mind, such a formalist position would elide the history of law and legal systems as a social response to the vicissitudes of power dynamics: international law and politics have never been fully separated, but remain in a mutually constitutive relationship. Law provides a framework for social relations and serves in turn to frame or generate them, in part; and, of course, law in its modern form remains an expression of political, moral and ethical choices channelled through processes which validate precisely those political choices and give them their legal form.

Framed thus, I advance the very basic point that international law, even if relatively autonomous from politics, remains an instrument within international society: an instrument for social change or for resistance, perhaps; but equally so, a powerful instrument in favour of the status quo, for the embedding and sustaining of past political choices—and the power relations which underlay those prior choices—into the present. International law and ‘high politics’ may make uneasy bedfellows, but they do not exist without one another.

So far, so formalist. But if we move to international courts and other adjudicatory bodies as institutions engaged with international law’s processing—what we variously call ‘interpretation’ or ‘application’—it becomes inevitable that international courts sometimes must engage in ‘high politics’, in the sense understood in this symposium. This definition is perhaps not that different from Ran Hirschl’s ‘mega-politics’, i.e., ‘matters of outright and utmost political significance that often divide whole polities’, a notion that Karen Alter and Mikael Rask Madsen have sought to apply to international judicial bodies.

The International Court of Justice, the ‘principal judicial organ of the United Nations’, is particularly visible when faced with high political situations. Whatever mirage might have been conjured by the Court’s consensual jurisdiction to shield it from potentially fracturing politics, it has been pulled into high politics by virtue of international law being invoked precisely in these periods of crisis. It is true that the Court has never weighed in on, and was perhaps shielded from, certain key crises of the UN period, such as the Cuban missile crisis, the Suez Crisis, the Six-Day War or the 9/11 attacks by Al-Qaeda. But equally true, the Court has been dragged into major turbulence over the years: the Iranian Hostages crisis; nuclear weapons (in 1974, 1996 and 2016); and most prominently, decolonisation and the problematic legacy of South African apartheid. It is no stranger to high politics, and its record is decidedly mixed.

In this tapestry woven with intermingling threads of international law and international politics, is there anything singular about our current period? Perhaps one doctrinal novelty over the last decade was the emergence of proceedings; in Fleur Johns’ evocative interview, embody ‘new articulations of community or common interests’ using the language of international law. These include advisory proceedings: in 2019, the decolonisation of Chagos Islands; in 2024, the situation of human rights in occupied Palestinian Territory; and pending, the advisory opinion on the consequences of climate change—perhaps the defining crisis of our time. Equally so, we see a surge of so-called ‘community interest’ or ‘common interest’ claims in contentious disputes: the genocide cases being brought by The Gambia against Myanmar and by South Africa against Israel; the torture case brought by Canada and the Netherlands against Syria; and of course the overwhelmingly Western interventions in the Allegations of Genocide case brought by Ukraine against Russia. These are buttressed by last week’s announcement, with actor Meryl Streep also speaking at the UN in a rather shrewd public relations move, that Australia, Canada, Germany and the Netherlands would file a claim against Afghanistan at the Court in relation to gender discrimination by the Taliban.

The legal issues brought to the table by these proceedings are rather straightforward. I remember coming of age and learning of the famous Barcelona Traction dictum on obligations erga omnes, acknowledged but not made operative in East Timor. Obligations erga omnes—owed ‘to all’—were a concept that had been midwifed into existence by the Court, but were not yet made whole. That task necessitated further efforts outside the Court, including the ILC’s drafting of Articles 41, 42 and 48 of ARSIWA as ‘progressive development’ (and then cursorily embraced as customary international law by the Court itself in Obligation to Prosecute or Extradite). I have written recently on the rather circular logic through which the Court, through its previous judgments, validated the crystallisation of the concept. In a sense, the concept of obligations erga omnes had come home: sent out to the world in 1970, it was bestowed with validation and concreteness in 2012. It has been suggested that the Barcelona Traction dictum is best understood as a sort of mea culpa for the Court’s catastrophic rejection of the legal interest of Ethiopia and Liberia against South Africa in 1966. Has the belated acceptance of obligations erga omnes (partes, at least) served as a form of redemption for the Court, if not for international law?

I am not so sure. It has not been lost on commentators that most proceedings asserting common interests seem to turn less on genuine community sentiment, rather than, again as Johns puts it, on ‘long-standing relationships of allyship and political allegiance’: The Gambia asserting protection over the predominantly Muslim Rohingya; South Africa leading a Southern resistance against Western-allied Israel; Canada and the Netherlands acting against Russian-allied Syria. It would be quite another thing if, for example, an EU member were to file a claim against another EU member for breaches of the Refugee Convention, or for some failure to ratchet up its carbon-emission reduction targets. Instead, what we see is a veneer of community interests, impelled by a mixture of perceived virtue—or arguably various competing visions of the universal—and tempered by a degree of sober self-interest; and all are channelled through the doctrine of obligations erga omnes. It is perfectly strategic litigation—ultimately, what litigation is not?—and it is not unpromising, even if its redemptive potential or paradigm shift is perhaps overstated.

But as with all doctrinal shifts—and this to me seems primarily a doctrinal advance—a few questions pose themselves at this juncture. The first is whether the various claims being brought by states across various developmental, ideological or historical divides embody some sort of renewed promise in the universality of international law, its ability to be deployed as an instrument against the international abuse of power. Tellingly, recent claims have been filed by actors in both the Global North and Global South, by the West and against the (broader) West. This may well reflect a fragile, conditional faith in the power of international law by those who have felt themselves to be held back by it. Yet a nagging caution continues to gnaw at me: can such claims genuinely embody a transformation (or transposition) of political struggles into the legal realm, strategically recast into the cool, apolitical language of claims, rights, duties and obligations, and away from brute politics. Or does that transposition into law inevitably lead to the reassertion of hegemonic (Western) conceptions of international law in what Martti Koskenniemi calls the ‘structural bias’ of international law, or what Sundhya Pahuja has suggested is the ‘critical instability’ that defines the relationship between political promises and the positive law? Or more cynically, does the range of states advancing such community interests at the Court simultaneously reflect both a continued faith in international law’s utility in resisting force and domination, and a clever tactic through which to reassert coherence and existing structures?

The second question: what the Court will make of all these various cases? Will it live up to the expectations of the claimants or requesting organs to bring international law into such politically fraught situations? It is perhaps no secret that the Court is relatively timid, if not outright afraid, of immiscing itself in tense and political cases. But such timidity is not usually found in its stolid maintenance, in its judicial pronouncements, of its role as a legal and judicial organ. It is found, rather, in the margins, in the language of certain dissentients; or, more discreetly, in the cautious amendment of its Rules in the aftermath of uncertain situations, as was recently done in the wake of the 33 requests for intervention in the Allegations of Genocide case.

But if international law is a ‘belief system’, can its ‘high priests’ successfully extend the authority of international law into such sites of political, economic or social struggle? Can the framing of urgent or violent disputes through the language of law suffice to bring about resolution or de-escalation, or at the very least, to turn the ‘international community’ against the culpable? Or will such cases, won in the courtroom, but never enforced, again illustrate international law’s relative impotence, and destroy any residual faith in the emancipatory potential of law? It is not for nothing that the Court’s methodological posture remains a resolutely formalist one, eschewing any claims towards progressive development and a sober emphasis on lex lata. This is not an avoidance strategy so much as an understanding of the limits of legal discourse in situations of high politics.

The dramas played out in the Great Hall of Justice are keenly observed by wider international society, or perhaps more specifically, the wider audience of international law scholars, students, practitioners, activists and other professionals who are watching. To those of us who understand the dynamics of the invisible college (whether at its core, at its margins, seeking access or even on the outside looking in), what David Kennedy calls the ‘struggle for expertise’ within international law circles seems to be sharpened by recent claims at the Court. I am less convinced though of their novelty: the relationship between law and politics is perhaps challenged, but these two argumentative modes oscillate between the famous apologetic and utopian poles. As the old cliché goes, old wine in new bottles.

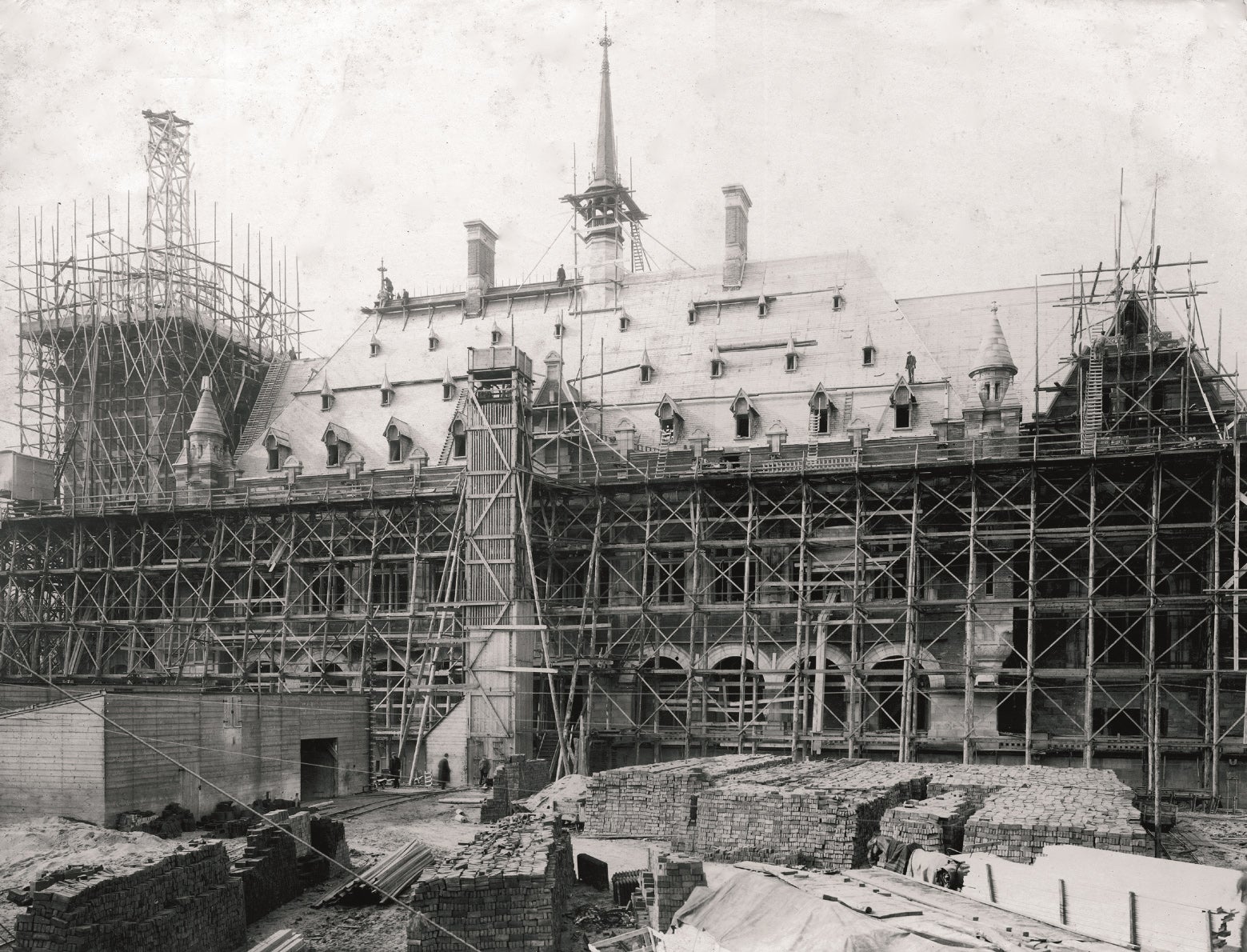

Finally, let us not underestimate the place of an unseen constituency, the general public: not for years has the Peace Palace been so visibly in the news, ranging from Aung Sang Suu Kyi defending her country 2019 to the audiences cheering on Carnegieplein as the Order on provisional measures was being read out against Israel in January 2024. Such claims seemed as much legal as they were choreographed performances, designed to invoke law’s purported objectivity but simultaneously using the courtroom as a dramatic setting, one to amplify and intensify moral and political claims. Law here served as a different sort of ‘instrument’: a vocabulary, a toolbox, but also a venue, a backdrop for clashes of a different nature. International law itself was the subject of dispute, and in an unusually public-facing manner. Faced with such public scrutiny, one wonders what the Court makes of it, and how it will eventually position itself: as a neutral, apolitical expert that is content to apply and interpret international law through its accepted and mainstream canons; a guardian of international law against its politicisation or instrumentalisation; or might it succumb to the glare of public attention and elide ‘speaking the law’ and ‘speaking truth to power’ with its own institutional vanity? ‘High politics’ bring to the table the potential for global attention to be drawn to the Court, and the international law it is meant to apply becomes a part of a wider narrative, and not its only task. But are the stakes higher because the world is watching; and will such public attention skew or somehow shift the outcome? After reading the interventions of Grietje Baars and Marina Veličković in relation to the Gaza case, I remain with the thought: is the battle also for the nature of international law itself?

In a burning world overcome with violence, but never bereft of hope, it is understandable why international lawyers turn to the key sites for international law to be made concrete, with the Peace Palace our enduring symbol of the faith placed in international law as a vehicle for international progress. Without any predictions, I suspect that the Court’s machinery will continue whirring as it always has, trying to safeguard its vocation as a site of legal struggle against the vicissitudes of politics. But I am not certain that the rest of international society will persist with such patience and faith in the legal process.

Gleider Hernández is Professor of Public International Law at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and President of the European Society of International Law.