International Fisheries as the ‘Whale in the Room’ at the BBNJ Negotiations

By Dr Ethan Beringen

Published on 11 March 2025

The successful conclusion of the negotiations for the new treaty on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ) was a significant achievement in international law making. This is especially the case given the divisions over key issues such as the status of marine genetic resources and the relationship between the new instrument and ‘…relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional, subregional and sectoral bodies…’ (IFBs), particularly the requirement that the new instrument should ‘not undermine’ these IFBs.

However, while the scale of the final instrument is impressive, the issue of high seas fisheries continues to be a question mark for the BBNJ. How can an instrument dedicated to the ‘conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction’ not include any direct measures related to the most significant source of marine biodiversity loss in the oceans? Indeed, the challenge of managing international fisheries can be considered the ‘elephant whale in the room’ at the BBNJ negotitations.

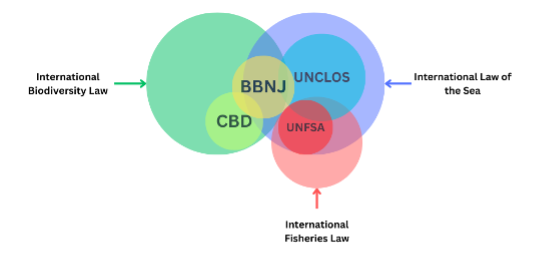

In response to this question, many will point to the existing United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA), another implementing agreement to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and argue that the matter is already settled under international law. Others may simply argue that the negotiations were already contentious enough without adding another issue in which there are significant vested interests. While acknowledging the influence of these factors, this blog post argues that the existing separation between the international fisheries law regime and the international biodiversity law regime meant that there was always going to be fundamental resistance to including any direct consideration of international fisheries in the BBNJ. This is especially the case as, in its form and content, the BBNJ instrument fits neatly with other international biodiversity law instruments such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), in many ways representing a coalescence of UNCLOS and international biodiversity law (See Figure 1 for a diagrammatic representation of the regime complex). There is still some cause for hope that the BBNJ, while not addressing fisheries directly, may serve as a coordination mechanism between existing high seas fisheries bodies, assisting them to more effectively conserve and sustainably ustilise marine biodiversity. However, for this to be successful, it is necessary to first understand the underlying dynamics present in the interplay between these regimes which is the focus of this blog post.

Regime interaction and regime-based narratives

International legal regimes have been defined as follows by Young:

‘…sets of norms, decision-making procedures and organisations coalescing around functional issue-areas and dominated by particular modes of behaviour, assumptions and biases.’

Furthermore, it has been argued by Hey that regimes have particular shared narratives (known as regime-based narratives) which can be understood to affect the modes of behaviour, assumptions and biases of actors within a particular regime. To understand the relationship between the international fisheries regime and the international biodiversity regime it is important to situate them in this context.

Of particular note are the fundamental governance principles within each regime as they have the ability to shape the development of a regime in a particularly path-dependent manner. Through an analysis of some of the fundamental principles of UNCLOS and the UNFSA on the one hand, as the foundation of international fisheries law, and the CBD on the other hand as the central instrument of international biodiversity law, it becomes clear that the two regimes have divergent regime-based narratives.

The divergence between the narratives of international fisheries law and international biodiversity law

This analysis highlights briefly some examples of the differing approaches between the narratives of the two regimes regarding fundamental questions. These are: what should be regulated, how should it be regulated and who undertakes the regulation and/or benefits from it?

On the issue of what there are clear overlaps between the mandates of UNCLOS, the UNFSA and the CBD in relation to the subject matter of their regulation. International fisheries law is most concerned with regulating targeted commercial species as well as those that are classified as dependent, associated, or non-target to some extent. Meanwhile, international biodiversity law in theory is applicable to all forms of life within the marine environment. However, in practice, the CBD is somewhat subordinate to UNCLOS as Article 22 of the CBD requires consistency with the ‘…rights and obligations of states under the law of the sea when implementing [the] agreement.’ This statement, given the context of the two regimes, seems a clear reference to rights and obligations regarding marine living resources, indicating that the CBD does not aim to interfere with such rights. Hence in practice, the overlap between the narratives of the regimes results in a demarcation of competences rather than coordination, ultimately leaving bodies such as Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) largely responsible for managing biodiversity on the high seas alone.

Divergences between the two regimes become increasingly apparent when looking at how they aim to achieve their goals. Both the UNFSA and the CBD state that their goal is the ‘conservation and sustainable use’ of their respective subjects but both regimes, though arriving at the same wording for their objective, reflect the political choices made at the time of their formation. In the case of the CBD ‘conservation and sustainable use’ is rooted in the popularisation of the principle of ‘sustainable development’ at the time of its creation (see e.g., Scholtz, the Rio Declaration, Agenda 21 and the Brundtland Report). This means ‘conservation and sustainable use’ under international biodiversity law can be seen as a means to address the developmental needs of current generations without affecting future generations’ abilities to meet their needs. Hence this goal is aimed at achieving this taking into account both economic, such as monetary or food security benefits, and intangible cultural and aesthetic values, such as the preservation of charismatic or culturally significant species and environments for future generations.

On the other hand, international fisheries law, while aiming for the same goal, finds its conceptual foundations within the initial principles laid down by UNCLOS regarding the optimum utilisation and maximum sustainable yield of fish stocks. While using the same language as international biodiversity law, international fisheries law is informed by these narratives when interpreting and applying the goal of ‘conservation and sustainable use’. Indeed, the concept of maximum sustainable yield is inherently focused on exploitation, but does not carry with it concerns over future generations or other inherent conservation values. Instead, it is purely an economic policy, or a ‘policy disguised as science’ which is concerned with maximum exploitation that can be sustained presumably indefinitely. This framing sees ‘conservation’ as a means to achieving the goal of ‘sustainable use’, which in turn is conceived as maximum sustained use. This distinction means that there is a different balance of priorities and hence, a different approach to how states aim to achieve this goal in international fisheries law.

Finally, on the who question, both international legal regimes are largely centred around state actors who are responsible for making decisions regarding the law, along with implementing and enforcing these decisions. The lack of a common narrative between the regimes can be partly attributed to differing state representation at these meetings, such as delegations from different internal government departments being present. Indeed, within the international fisheries regime, delegates are likely to be from national fisheries departments, whereas, in international biodiversity law, interests from environment departments may be present instead. The participation of non-state actors may also diverge, with the fisheries industry overrepresented within fisheries bodies, while conservation and development NGOs may participate more often in the international biodiversity law regime. In addition, states shape these narratives within distinct regimes in a way that allows them to arrive at a regime that best serves their interests. It is likely then that the drive to keep effective separation between the regimes comes from states with particularly strong interests in fisheries, as well as fisheries industry representatives.

Looking to the future for the BBNJ and fisheries

It is clear that the BBNJ agreement as a new part of the international biodiversity regime has been both consciously and unconsciously kept separate from international fisheries law, despite compelling reasons for robust connection and collaboration. The role of entrenched narratives stemming from the foundational instruments of these regimes cannot be discounted in understanding why the final form of the BBNJ instrument does not directly address fisheries.

This blog post focuses on these dynamics as understanding the relationship between these regimes will be crucial for the success of the BBNJ in interfacing with international fisheries bodies going forward. The extensive role demarcated for IFBs in the process of the design of area-based management tools such as marine protected areas for example may provide an indirect means of including international fisheries issues in the BBNJ regime. Additionally, the provisions on ‘not undermining’ also contain positive obligations for the BBNJ to promote ‘coherence and coordination’ between these IFBs. There is even the potential for the new Conference of the Parties to set up processes through which RFMOs may coordinate closely both with the BBNJ and amongst one another. Indeed, the BBNJ specifically empowers it to do so. Hence the BBNJ may not address fisheries explicitly, but it may yet serve as a vehicle for greater coordination between and amongst fisheries bodies.

This blog post has demonstrated however that such hopes should be tempered by the history of the interaction between these regimes. There is a clear divergence in the narratives of the two regimes which results in a lack of willingness to fully consider fisheries regulation as being within the remit of international biodiversity law. It is hoped this research may shed some light on the role these underlying narratives play in shaping international law, as well as demonstrate that points of commonality and overlap between regimes should be acknowledged and clarified in order to build better international law for the protection of the marine environment. After all, the first step to dealing with the ‘whale in the room’ is understanding why nobody wants to talk about it.

This blog post is based on: E Beringen, ‘International fisheries as the ‘whale in the room’ at the negotiations for a new instrument for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction’ to appear in The Law of the Sea and the Planetary Crisis, Nengye Liu and Shirley V Scott (eds) (Routledge 2025).

Ethan Beringen is a Yong Pung How Research Fellow at Singapore Management University.