International Order and the Politics of Freedom of Information in Chile

by Wanshu Cong

Published on 21 December 2023

This post considers Allende’s socialist revolution in Chile as one of the earliest and toughest battles for not only a more just and equal international economic order but a more democratic and people-empowering structure of international information flow. This latter struggle of Allende’s Chile, surrounding domestic and international mass media practice, the structure of international communication, and the power imbalance between states and transnational media and telecommunication corporations, encapsulated all the crucial challenges and demands that would later characterise a movement, known as a New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO). The NWICO movement, initially started as an effort to enhance cooperation and mutual understanding between Non-Aligned countries, achieved significant momentum at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in the late 1970s. It strived to strengthen the informational and communication capacity of the Global South, and to equalise information flow between the North and the South. It contested the prevalent market-oriented and individualist conception of freedom of information and redefined it as a collective right integral of the broader de-colonial and developmental agenda of the Global South. By the time UNESCO adopted the MacBride Report and related resolutions about NWICO at its 1980 General Conference, Allende’s government had long been replaced by the military dictatorship. However, the Chilean experience during Allende had left a visible impact on the NWICO movement and indeed continues to inform post-NWICO projects of democratising international communication and the international order more generally.

‘A free marketplace of ideas’

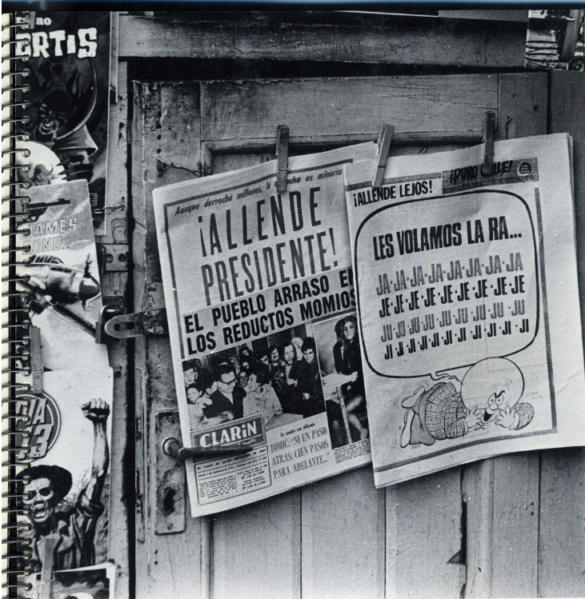

Allende envisioned Chile’s socialism as one built within and through its pre-existing constitutional and democratic framework. ‘In Chile there is not a single political prisoner, nor the least restriction on oral or written forms of speech’, Allende said at the inaugural ceremony of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) III. If one judges the level of freedom of information in a country according to the degree of governmental control and censorship, Chile under the Popular Unity government would no doubt rank as one of the freest. Not only did the government tolerate the growth of anti-governmental media and opinions, it also did not curb the increased import of US originated entertainment products. One state channel and three university channels were also commercialised during Allende’s years. Herbert Schiller observed that the Allende government tolerated a ‘relatively pure model of a free marketplace of ideas’ in Chile.

And yet, in this ‘free marketplace’, conservative press in Chile and the region, with generous funding from the US Central Intelligence Agency, had been relentlessly attacking Allende and Popular Unity even before Allende’s election. El Mercurio, for example, an anti-governmental newspaper with the largest readership in Chile, had received $1.5 million from the CIA since Allende’s election. In the collusion between the Chilean conservative media and the CIA lies an obvious lesson about the role, or indeed responsibility, of mass media in a country’s political stability and independence, which reappears as critical in our ‘post-truth’ era.

However, only thinking of the Chilean lesson as one about foreign interference through mass media propaganda distracts us from a more fundamental critique about the notion of freedom of information and the free marketplace of ideas. What the Chilean experience demonstrates is the inherent power relation in the production, circulation, and consumption of information, which is often concealed by the commonplace image of ‘marketplace’ and ‘free flow’ of ideas that presents information as simply apolitical. In Chile during the 1970s (and indeed, before and after Allende), this ‘marketplace’ has always been one of the information monopolies, by these monopolies, and for these monopolies. Formal (or rather, formalistic) democracy which preserves the essentially bourgeois right of freedom of information and leaves intact the power relation in and of information flow is ultimately inimical to the real democratisation of communication.

Looking back at Allende’s Chile, the contrast between the remarkable stride of nationalisation of major economic sectors and the untouched monopolistic power of domestic and foreign mass media is striking. I do not use the word ‘monopoly’ here in a strictly legal sense, but the point is to highlight, first, the merchandised character of information, and second, the sheer disparity between those who own or control information products and communication networks and those who don’t, which structures this ‘marketplace’. NWICO advocates, such as Mustapha Masmoudi, criticising the domination of western news agencies, argued that ‘freedom of information’ in effect was ‘the freedom of information agent’ to transmit and disseminate information unhinderedly and that people of the Third World were rendered ‘mere consumer of information sold as commodity like any other’. The observation about information as a commodity applied not only to news but to other information products generated from western capitalist countries such as books, television and radio programs, and films, of which the whole lifecycle was built for profit-making. Chile, and Latin America more broadly, had always been a fertile and lucrative market where American originated materials were consumed much more than those locally produced.

Informational imbalance as obstacles for radical social change

Masmoudi’s comment also directs our attention to the unequal relation between communicators (or ‘information agent’) and audiences. Significantly, this asymmetry was intrinsic to and constructed by the very media of communication, such as television and satellite broadcasting developed in the 1960s and 1970s, which was unidirectional, making communication the exclusive right of the transmitter. In Chile and indeed the large hinterland of the US’ informal empire, this inequality of communication and information flow was further translated into domination in all aspects of the society’s political and economic life. In addition to the outright anti-Allende propaganda and ‘scare campaigns’, cultural critics in the region (for example, Dorfman and Mattelart’s pioneering work, ‘How to Read Donald Duck’, a Marxist take on Disney cartoons’ promotion and reinforcement of capitalist and imperialist ideology in Chile) had long pointed out that media programs from western capitalist countries imposed consumerist values of dolce vita on the audiences, and that such values were not only alien to the local cultures and morals but created escapist or defeatist sentiments and hypnotised the masses, which were detrimental to the society’s socialist transition and development.

The political consequence of such informational imbalance was obvious, but the Allende government’s response was not unequivocal. In the international plane, Chile was one of the most vocal proponents for the UN to regulate direct satellite broadcasting in the early 1970s, seeing this technology as enabling another frontal attack by imperialist information monopolies on the country’s cultural integrity and political independence. Domestically, however, Allende’s government, having pledged to respect freedom of expression, did not socialise media ownership. Instead, the government endeavoured to diversify the import of foreign cultural products and to create publishing houses such as Quimantu to offer low-priced educational materials to Chilean workers. Other forms of political communication by the left included protest songs, dancing performances, poetry reading, theatre plays, and mural painting. These grassroots, face-to-face communication strategies for mass mobilisation later inspired communication scholars during NWICO to expound ideas such as ‘horizontal communication’ based on democratic social interaction and broad participation, and the idea that such democratic communication should incorporate traditional techniques (such as oral tradition) rather than solely relying on modern mass communication technologies. However, during the three years of the Popular Unity government, ingenious as these efforts were, in hindsight they proved too piecemeal to shake off the domination of conservative mass communication. Contemporaneous commentators even saw Chile as a lost battle of the left for the mass media struggle.

‘Free flow of information’ and the international order

Not only was domestic mobilisation hampered by the lack of effective mass communication, the government also found it hard to garner international support. As Allende told the UN in his 1972 speech at the General Assembly, ‘we realize that when we denounce the financial-economic blockade with which we were attacked, it is hard for international public opinion and even for many of our compatriots to easily understand the situation’. This was echoed by many other Global South countries who complained about the difficulty in communicating with each other and the rest of the world due to the monopolistic control of information networks by western news agencies. Here comes another crucial lesson from the Chilean experience, which is that radical social change requires not only communication strategies but the accompanying revolution of the media structure and changes in the modes and relations of production that constitute information flow domestically and internationally. This often calls for substantial investment and intervention of the state to circumvent informational monopolies, by creating alternative communication channels and mutual resource sharing with other countries having similar demands (an example being the Non-Aligned News Agencies Pool). The point here is that mass communication is more than a key field where battle for radical social change is waged but its own restructuring is indispensable for such change.

In the Chilean experience, in addition to the imbalance on communication content, the inequality in the communication process and information flow was also amplified by the fact that communication systems and infrastructure in the region were often built and operated by American companies. Such a reliance demonstrates another critical layer of the power relation undergirding ‘the free flow of information’. This was indeed not unique to Latin America, as most postcolonial countries had remained largely dependent on the old imperial telecommunication systems for international communication. As Allende remarked in his inaugural address to UNCTAD III, ‘seventy-five per cent of [the international telecommunication system] is in the hands of the developed countries of the West, and of this proportion, more than 60 per cent is controlled by the big United States private corporation’. In his speech at the UN General Assembly, Allende further named an American telecommunication company, International Telegraph and Telephone company (ITT), along with the Kennecott Copper Corporation, as the ‘central nucleus of the large transnational companies that sunk their claws’ in Chile and accused them of trying to dictate the Chilean political life.

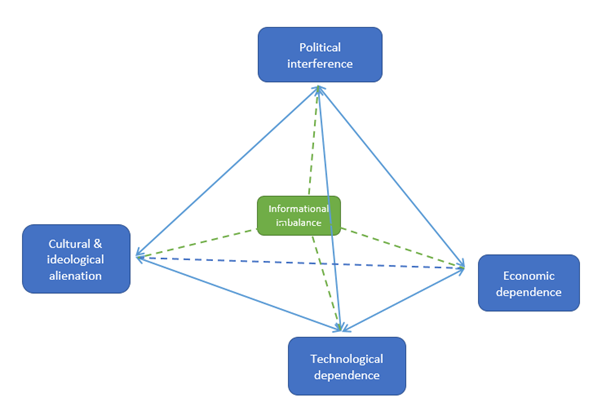

The ITT had been operating in Chile since 1927 with a fifty-year concession and enormous political connections. It is ranked by business historians as one of the most hated companies in history. The ITT’s history in Chile and the exposé about its plot with the CIA against Allende testifies the political clout of such major transnational corporations and their essential role in preserving imperialist relationship between the North and the South. Moreover, the long process of expropriating the ITT in Chile (which was contemplated by the Frei government and completed actually after the military coup) largely overlapped with the years of building Chile’s national telecommunication network, Entel. This twin process demonstrates that the struggle of obtaining control over communication networks, and hence rectifying informational imbalances, is simultaneously one against economic dependence and political interference.

The intertwinement and mutual perpetuation of these variegated elements of imperialism—the political, the economic, the technological, the informational, the cultural and the ideological—is the most fundamental insight that Allende’s Chile provides. This was reflected later during the NWICO debate which elaborated NWICO and NIEO as ‘indissolubly linked’, one serving as the precondition and sine qua non of the other, and together forming the same battle of decolonising the existing international order.

Information as power

One way to summarise the gist of the story about Allende’s Chile and the NWICO is perhaps to recall the classic dictum by Foucault about the knowledge/power nexus—the idea that knowledge emerges from relations of power and is itself a form of power—cliché as this may sound. But in the Chilean story, it is hard to talk about the ‘productive’ aspect of power in the Foucauldian sense or to see unequal social relations as merely products of discourses transmitted through mass media, while leaving aside the tangible, material brutality associated with mass media practice backed up by powerful transnational corporations and their home countries. The Chilean story shows information and the whole social relations surrounding the production and communication of information as both an outcome of a violent and imperialist international economic and political order and an essential part of the fight against that order. Fifty years after the end of Allende and the Popular Unity’s attempts, there have been obvious changes in media and information technology (e.g., the change from top-down mass communication to multidirectional social media, the development of the internet and web 1.0 to 4.0, etc.), and the political landscape of the world (e.g., the bankruptcy of the ideology of developmental postcolonial state in the left and the rising of new forms of transnational grassroots movements). Yet, the Chilean story and its many lessons about the politics and power of information remain significant and pertinent for the agenda of democratising international order today when new communication technologies and digital data flows become not only regulatory objects but embody tremendous geopolitical stakes.