Just Transitions and the UN Secretary-General’s Panel Critical Energy Transition Minerals Recommendations on “Resourcing The Energy Transition Principles to Guide Critical Energy Transition Minerals Towards Equity and Justice”

by Railla Puno (Associate Lead, Climate Change Law and Policy, CIL) and

Danielle Yeow (Lead, Climate Change Law and Policy, CIL)

With acknowledgements and thanks to Rayson Ng

(CIL Student Researcher, Climate Change Law and policy) for research and drafting support.

The concept of just transition originated in the 1970-1980s when North American trade unions developed a framework to protect the jobs of workers in industries that were impacted by new air and water pollution regulations. Trade unions sought to align their efforts to provide workers with decent jobs and protect the environment—using the term just transition to describe the interventions required to give workers secure jobs in the shift from a high to a low carbon economy. This has evolved over time and has in recent years directly linked to climate action. Just transition under the UNFCCC recognises that climate action has indirect consequences on workers and communities that are dependent on the fossil fuel industry and requires that measures to be put in place to ensure that climate action is done in a fair and inclusive manner, leaving no one behind.

A. Just Transitions under the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement explicitly included consideration for just transition in the Preamble where it states: “taking into account the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities”. At COP 27 in 2022, the Work Programme on Just Transition Pathways (WPJTP) was established to design pathways to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement in a way that is just, equitable, inclusive, and considers national capabilities and sectoral and communal circumstances. A Dialogue was also established to be held twice a year to discuss views and share knowledge on various issues.

During the first Dialogue held in June 2024, Parties and Observers discussed just transition pathways to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement through the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), and the Long-term Low Emission Development Strategies (LT-LEDS). As of 2024, only 38% of NDCs and 58% of LT-LEDS refer to just transition principles even though an estimated 78 million workers are set to be affected by the transition to a low carbon economy.

The second Dialogue held in October 2024 focused on ensuring support for people-centric and equitable just transition pathways focusing on the whole of society approach and the workforce. This Dialogue emphasised the need to include all actors and segments of society and the role of international cooperation and partnership to achieve just transition. As UN Climate Change Executive Secretary Simon Stiell said: “Just transition means different things to different people depending on who they are and where they live. But one thing is certain: we cannot and will not leave those with less power and marginalised groups out of the picture. Solutions to the climate crisis are meant to be inclusive.”

The Informal Summary Report of the Second Dialogue also shows that critical minerals are increasingly becoming a major concern for many Parties. Some Parties reflected on unequal benefits from resources, particularly from the extraction of critical minerals and the localisation of profits from those extractions. They highlighted the need for technology cooperation and transfer in this field and the need for additional research on local resources, especially critical minerals, to empower science-based policymaking.

B. UN Secretary-General’s Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals

‘Critical energy transition minerals’ refer to the minerals necessary to construct, produce, distribute and store renewable energy. They include a wide array of minerals including copper, cobalt, nickel, lithium, graphite, rare earth elements, aluminium, chromium, zinc, silicon, cadmium, tellurium, and selenium. These are required for production of electric vehicles and battery storage; solar panels, and wind turbines to name a few.

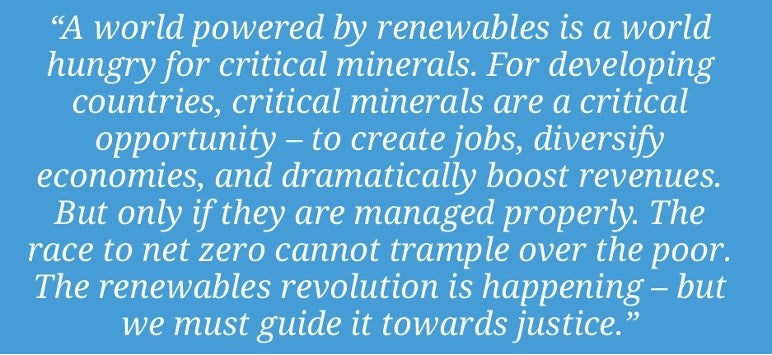

At COP28, Parties agreed to triple the global renewables capacity and double energy efficiency by 2030. Achieving the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement is contingent on a sufficient, reliable and affordable supply of critical energy transition minerals which are essential components of clean energy technologies. According to the International Energy Agency’s Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024 report, mineral demand for clean energy technologies is estimated to triple the demand for critical energy transition minerals by 2030 and quadruple by 2040 on a nett zero CO2 emissions by 2050 scenario. This offers tremendous economic opportunities for countries that possess such resources, including developing countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Pacific, to generate prosperity, eliminate poverty and drive sustainable development. At the same time however, a transition of such magnitude can bring substantial challenges.

First, mining at all scales have often been linked to pollution, environmental degradation, human rights abuses, adverse impact on the rights and interests of indigenous and local communities, as well as geopolitical tensions and instability. Many developing countries that possess large reserves of such minerals often lack processing capabilities to add value and end up at the bottom of the value chain. UNCTAD estimates that commodity dependence, which can hinder economic development and perpetuate inequalities and vulnerabilities, affects 66% of small island developing states, 83% of LDCs and 84% of landlocked developing countries. There is a need to properly manage the mining of critical energy transition minerals, to avoid perpetuating commodity dependence and posing environmental and social challenges. Second, the supply-demand imbalance, coupled with market concentration of supply and refining capacity can lead to price spikes and volatility which in turn threatens the speed of energy transition and heightens the risks of supply chain disruptions.

As the global community strives to secure a significant increase in the supply of critical energy transition minerals, such concerns should be addressed in order to ensure that the increased supply do not come at the expense of the environment or indigenous and local communities, provide for an equitable and just pursuit of opportunities of the global energy transition, support sustainable development, and is delivered via responsible, fair and just value chains. Rather than serving only as providers of raw materials, developing countries operating as partners in the energy transition can foster development through opportunities for value addition, benefit-sharing, economic diversification and participation in the critical energy transition minerals value chains.

Against this backdrop, and in response to developing countries’ call for action, the UN Secretary-General’s (UNSG) Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals was established in April 2024 and tasked to develop a set of “global and common voluntary principles on issues which are key to building trust between governments, communities and industry, enhancing transparency and investment, and ensuring just and equitable management of sustainable, responsible and reliable value chains for terrestrial critical energy transition minerals.” Co-chaired by Ambassador Nozipho Joyce Mxakato-Diseko of South Africa and Director-General for Energy Ditte Juul Jørgensen of the European Commission, panel members, who were nominated by governments, intergovernmental and international organisations, and non-state actors, were appointed by the UNSG and participate in their personal expert capacities.

UNSG António Guterres

C. The Panel’s Recommendations

The Panel issued its report on 11 Sept 24 titled “Resourcing the Energy Transition Principles to Guide Critical Energy Transition Minerals Towards Equity and Justice” and proposed a set of seven Guiding Principles and five Actionable Recommendations (GPAR) that aim to foster trust, justice, equity, diversified supply chains as well as to enhance trust and investments across the critical energy transition minerals value chain. Collectively they “aim to empower communities, create accountability, and ensure that clean energy drives equitable and resilient growth. That includes advancing efforts to ensure maximum value is added in resource-rich developing countries.”

Drawing from existing international legal principles, norms and political commitments, the Panel articulated seven Guiding Principles as follows:

- Human rights must be at the core of all mineral value chains

- The integrity of the planet, its environment and biodiversity must be safeguarded

- Justice and equity must underpin mineral value chains

- Development must be fostered through benefit sharing, value addition, and economic diversification

- Investments, finance, and trade must be responsible and fair

- Transparency, accountability, and anti-corruption measures are necessary to ensure good governance

- Multilateral and international cooperation must underpin global action and promote peace and security.

The Panel also put forward 5 Actionable Recommendations to operationalise and support the implementation of the Principles:

- Accelerate greater benefit sharing, value addition, and economic diversification

- Launch a process to develop a global traceability, transparency, and accountability framework

- Create a Global Mining Legacy Fund

- Empower artisanal and small-scale miners

- Launch process to implement material efficiency and circularity approaches to balance consumption and reduce environmental impacts

The GPAR are extensive and comprehensive in nature, covering the entire life cycle of the critical energy transition minerals. Recalling the Sharm El-Sheikh Implementation Plan, the WPJTP, and the first and second Dialogue on the WPJTP, the Guiding Principles and Recommendations are aligned with the concepts and elements of just transition.

D. Implications of the GPAR

What then are the potential implications of the GPAR for governments, corporates and civil society? Governments for instance may embed elements from the GPAR and recommendations in their domestic regulatory and licensing policies and frameworks, such as the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. They may review fiscal and investment policies relating to the extractive sector to ensure benefit sharing among affected communities, ensure consistency with international trade rules in the use of export controls and restrictions on critical energy transition minerals and the on-shoring of mineral value-added processing activities, and collaborate with other Governments via joint investment frameworks to support investments in the extraction and processing of critical energy transition minerals, while also promoting responsible extraction, circularity and sustainability of the mining industry and supply chains. Examples of such collaborations include the South African partnership on minerals for future clean energy technologies and energy transition and the Memoranda of Understandings between the EU and Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia to develop cooperation in five key areas of the critical raw materials value chain.

Further, in line with Principle 7, governments should work together through international forums to coordinate global efforts toward a Just Transition. Multilateralism is key with international and International and regional cooperation vital to ensuring that critical energy transition minerals do not become a source of tension and conflict.

Multilateral developments banks and financial institutions that provide financing for critical energy transition minerals mining and refining projects should also consider integrating into their lending criteria, requirements that the projects support responsible environmental, social and governance practices, embed circularity in their processes and supply chains as well as enhancing the industrial capacities of the resource rich developing countries.

In the case of corporates engaged in the critical energy transition minerals mining sector or supply chain, businesses can consider reviewing and aligning their policies, processes and practices in line with the GPAR. This may include integrating the transparency and accountability measures, deploying sustainable mining and processing technologies, and benchmarking and adopting voluntary standards to safeguard environmental, workplace health and safety, labour and human rights standards. They could also support workers, indigenous and local communities who are adversely impacted by the clean energy transitions and conduct effective, meaningful consultations with all relevant stakeholders; and conducting human rights due diligence in mineral value chains.

Civil society also has a crucial role in ensuring the inclusive and equitable transition, for example in fostering dialogue and serving as a vital bridge between communities, businesses and policymakers. For example, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC)’s Just Transition Centre has facilitated dialogue among stakeholders in South Africa and Indonesia, leading to significant policy reforms and an enhanced role for workers in the transition process.

In addition, the Recommendations, such as the Global Mining Legacy Fund, as well as the development of a global traceability, transparency and accountability framework are far-reaching in nature, and will require multilateral and international cooperation as well as effective public-private collaboration to truly deliver the goal of “equity and justice” in relation to critical energy transition minerals in the energy transition.

E. Ways Forward

The GPAR is not a state negotiated instrument and are undoubtedly in the nature of non-legally binding recommendations and principles. Nonetheless, we should not discount their significance and import as they reflect the consensus views of experts from geographically diverse governments, international governmental organisations, as well as non-state actors. Notably, the Panel was careful to emphasise that the Recommendations and principles are built on existing international norms and legal obligations e.g. in the field of human rights obligations.

The Panel has invited the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), all the Special Procedures of the UNHRC and Treaty Bodies, and other relevant institutions, e.g. ILO, to integrate GPAR into their work and to use their accountability instruments to monitor and ensure human rights and labor rights compliance in critical energy transition mineral value chains and the protection of environmental human rights defenders and environmental defenders, with particular attention to safeguarding vulnerable groups and the individual and collective rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The UNSG has also tasked the Co-Chairs and Panel to socialise the GPAR with Member States and other stakeholders ahead of COP29. During the COP29 Special Event held on 13 Nov 2024, “High Level Meeting on Resourcing the Energy Transition with Justice and Equity: Advancing the recommendations of the UNSG’s Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals,” the UNSG announced that the UN system is coming together to help implement the Panel’s findings, including to establish the recommended High Level Expert Advisory Group (HLEAG) and to take forward the global recommended global traceability, transparency and accountability framework for the entire mineral value chain. Statements delivered during the Special Event signalled support for the Report and broad support for advancing the recommendations. UNEP and UNCTAD are expected to play a leadership role in this process given the subject matter. In the meantime, views have been invited on the appropriate composition of the HLEAG as well as its mandate. The declared goal is to complete the process and work of this HLEAG by the ambitious timeline of the 1Q2025.

Looking ahead beyond the work of the future HLEAG, it is conceivable that the Panel’s Recommendations may be integrated in relevant multilateral-making processes such as the WPJTP, or even plurilateral initiatives and declarations on the sidelines of future UNFCCC COPs. In line with the Panel’s invitation, the Recommendations could also be integrated into the future work and accountability mechanisms of other UN human rights processes as well as featuring in other platforms such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Bodies such as the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights may also reference and incorporate the Recommendations in their future deliberations on the extractive sector, just transitions and human rights.