Symposium: Use of force, territorial integrity, and world order: continuing the debate

On force, territory, and independence:

how (not) to narrow down a rule

by Anastasiya Kotova & Dr Ntina Tzouvala

Published on 24 March 2023

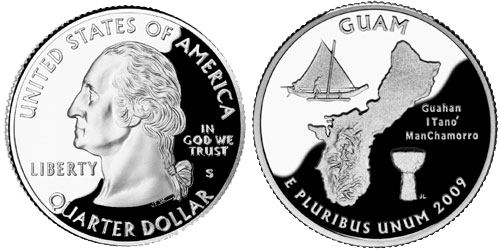

In analysing the legal and political implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Ingrid (Wuerth) Brunk and Monica Hakimi suggest that the invasion has thrown the light on the importance of the ‘the norm at the core of the UN Charter system on the use of force: the prohibition of forcible annexations of foreign territory’ (p. 689). It is for this reason, they argue, that Russia’s aggression constitutes one of the biggest—if not the biggest—challenges to the post-World War II international (legal) order (p. 691). Even though we do not necessarily disagree with this conclusion, we are not convinced about singling out one part of Article 2(4) (namely territorial integrity) over the letter and spirit of the provision that places territorial integrity alongside political independence and prohibits the use of force against both. Our concern is that defining the norm at the heart of the international legal order ‘in the negative and in the most minimal possible terms’ (p. 689) risks (re)creating an international legal order after the image of US imperialism, an imperialism that at least after 1945 is less focused (albeit with notable exceptions, especially in the Pacific) on territory and more reliant on force against political independence. In other words, we can (and should) be attuned to the distinctiveness of Russian imperialism and its territorial bend without turning this distinctiveness into moral and legal hierarchy.

The principle of prohibition of the threat or use of force includes as its normative content a range of norms. An overview of those can be obtained from the Friendly Relations Declaration, which is declaratory of customary international law, according to the International Court of Justice. Those include prohibition of threat or use of force against (1) territorial integrity and political independence of a State and (2) any use of force ‘inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations’, as well as a range of prohibitions on the indirect use of force, such as organising and sending armed bands and mercenaries. Brunk and Hakimi single out the prohibition of forcible annexation among those as ‘the holy grail of the post-World War II order’ (p. 689). Several explanations as to the special status of the prohibition of territorial annexation can be deduced from their argument. One such explanation is that prohibition of territorial annexation appears to lie at the intersection of several Charter principles, namely the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples and the principle of sovereign equality: if we were to make a Venn diagram of those principles, it is, indeed, the prohibition of annexation that would lie in the middle.

However, the fact that forcible annexation of territory violates other principles in addition to that of the non-use of force does not as such grant any special status to the prohibition of annexation compared to other prohibited uses of force. As multiple military interventions of the US, the UK, and North Atlantic Treaty Organisation partners (on some occasions) show, the right of people to self-determination, as well as territorial integrity and political independence of a state having the sovereign authority to represent them, can be violated just as severely without any claim laid on their territory. The conduct of Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) in Iraq is an apt demonstration: by violently overthrowing Iraq’s government, overseeing the breakdown of law and order, forcing Iraq on the path of accelerated neoliberal transformation, and making these reforms hard to reverse both in terms of law and in terms of practicality, the CPA virtually removed fiscal, tariff, and monetary policy from the domain of democratic deliberation. It is, after all, worth recalling that the Nicaragua case, which continues to be a principal point of reference about jus ad bellum for many international lawyers, did not concern an attack against the country’s territorial integrity but a co-ordinated campaign against its political independence in ways that were representative of a broader pattern of imperialism deployed by the USA in the Americas, especially against left-wing governments.

One explanation of this focus of US force on political independence (and not territorial integrity) has been offered by Daniel Immerwahr. While highlighting the forgotten history of US territorial imperialism, Immerwahr also observes the sharp decline of its significance after 1945. In this telling, the rapid improvement of logistics during and due to World War II enabled economic exploitation without full territorial control. This was a happy coincidence as the rise of Third World nationalism rendered formal empire politically troublesome and financially unsustainable. Since then, US imperialism has operated through coups, containers and investment treaties rather than outright annexations (again, though, Pacific Islanders have a more complicated story to tell). Therefore, a reading of Art. 2(4) of the UN Charter that emphasises territorial integrity over political independence is a reading that tracks closely (intentionally or not) the transformations of US imperialism and sees degrees of illegality where we should see changes in political economy fuelling different forms of imperial violence. In addition, Russia’s attempt to annex Ukrainian territory is less unprecedented than one might have preferred: there are, unfortunately, multiple instances of (attempted) territorial annexations in the period after World War II, starting from Palestine, Tibet, to the Golan Heights, Western Sahara, and East Timor. In fact, the Israeli Knesset recently passed a bill transferring the authority over the occupied West Bank from the Ministry of Defence to the Ministry of Settlement, effectively accelerating its ‘slow annexation’.

Nevertheless, we do think that Russia’s annexationism is both politically and legally distinct, but for different reasons than those put forward by the American Journal of International Law’s editors. First, as we alluded to in an earlier contribution, a more direct reliance by the capitalist elite on the state for continued accumulation in contemporary Russia is distinct from other forms of capitalist states. In what is often referred to as ‘Bonapartism’ by Marxist scholars, Russia’s state apparatus intervenes directly in capitalist relations ensuring the continuing enrichment of political allies but without giving them political power in their own right. Combined with extractivism, this form of capitalist statehood means that direct territorial control is necessary (or at least much more convenient) for the continuing operation of this economic model. Secondly, annexationism combined with Russia’s rhetoric is important when viewed from the perspective of Ukrainians themselves. As others have noted, the denial of legitimacy of Ukraine as a state and of Ukrainian identity as a whole (as opposed to denying the legitimacy only of the present government, as many imperialist powers have done in the past) is the ideological justification of this attempted annexation. This rhetoric constitutes an outright denial of Ukrainians’ most basic right to self-determination. Worryingly, read together with the widespread use of derogatory hate speech in Russian media, it can be argued to amount to the existence of genocidal intent amongst Russian civil and military leaders. This is, of course, important both in general and, in terms of international law, since it potentially engages the prohibition of genocide, a jus cogens rule. This grim realisation though should not lead us to ‘read down’ either the prohibition of the use of force or the right to self-determination in ways that place territory over a people’s right to effectively decide on its own destiny.

Arguably, we would not be entirely alone in so doing. As Rose Parfitt, Sundhya Pahuja and Tracey Banivanua-Mar have all argued, international law limited the outcomes of decolonisation by promoting statehood as the only valid form of self-determination, in a process that, amongst other things, disadvantaged profoundly Indigenous peoples both in the Global North and in the Global South. However, the fact that this fixation with territory has deep roots in international law does not mean that it should be extended to circumscribe the application of rules that, thanks to the struggles of colonised peoples themselves, were articulated and continue to be understood in more comprehensive terms.

The claim that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is different in kind than use of force by the Western states is also derived by reference to the practice of the latter, particularly their reliance on the exceptions (generally recognised and less so) to the Art. 2(4) prohibition—whether in course of ‘humanitarian intervention’ in the former Yugoslavia or of the ‘war on terror’. Prohibition of territorial annexation is, then, granted special recognition because states that violated the general prohibition of the use of force refrained from annexing foreign territory. However, as we argued above, an alternative explanation is readily available. Western imperial powers did not resort to annexation because they did not need to: the combination of military bases all around the world, advanced logistics, international economic and commercial law, as well as targeted uses of force, means that they can exercise significant degree of control over other political communities through the post-World War II institutional architecture. Whether the Western states refrained from territorial annexation for normative or pragmatic reasons, the practice of those states, including the fashioning of exceptions to the non-use of force, are, perhaps, more indicative of their attitude towards international law than of the content of international legal rules. Their narrow approach to the construction of the relevant principles was not widely shared by ‘the rest’. Indeed, the fact that a significant number of states have decided to remain relatively uninvolved in this conflict—without being Russian satellites or even its allies—speaks to the fact that efforts to distinguish between Russian and US imperialism do not have universal appeal.

Widespread condemnations of Russia’s aggression as such are, in our view, a net positive for international law and politics. This is because, as Samuel Moyn has argued, the past three decades have witnessed a shift in emphasis: the promise of ‘humane’ war overshadowed efforts to eliminate or at least limit armed conflict—a prioritisation that was reflected, amongst other things, in the Rome Statute. In our minds, it is imperative that this re-centring of the evils of aggressive war does not become defanged by a simultaneous introduction of textually, historically and politically unsustainable distinctions in Art. 2(4) of the UN Charter.