Salvador Allende, Populism and An International Law of Solidarity

by Dr Claerwen O’Hara and Dr Valeria Vázquez Guevara

Published on 19 December 2023

Today, populist politics are often depicted as hostile to international law. Specifically, there is an assumption that populism favours nationalism over multilateralism and has an antagonistic relationship with international institutions. However, as scholars such as Christine Schwöbel-Patel and Marcela Prieto Rudolphy point out, the conflation of populism with nationalism reflects a Western-centric mode of thinking. Across the global South, and in Latin America in particular, there is a long tradition of combining populist politics and internationalism. Chilean President Salvador Allende, a democratically-elected Marxist who emerged as one of the most influential Third World leaders of the-twentieth century, is someone who unsettles the contemporary ‘populist versus internationalist’ binary. Throughout his political career, Allende consistently based his politics around an idea of the ‘people’. Drawing on the work of political theorists Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, we argue that this reflected a form of ‘left populism’. At the same time, Allende never lost sight of the international. Instead, he was a staunch advocate for solidarity between the ‘peoples’ of Latin America, the South, and other parts of the world too. In this post, we pay tribute to one of the legacies of Allende’s people-oriented internationalism: his articulation of an international law of solidarity.

Allende and the ‘People’s Government’ of Chile

To understand Salvador Allende’s vision of an international law of solidarity, it is first necessary to understand his people-centred politics in Chile. Allende was elected President of Chile in 1970, as the candidate of a broad left-wing coalition known as the Unidad Popular (Popular Unity). While his election was tight, there was widespread popular participation in Allende’s presidential campaign. For example, Unidad Popular became linked with the Chilean nueva canción (new song) movement, allowing ordinary Chilean people to mobilise in favour of Allende through the singing of political folk songs, such as ‘El pueblo unido jamás será vencido’ (The people united will never be defeated). Once President, Allende described his government as the ‘People’s Government’ and nationalised the country’s iron, steel, coal, nitrate and copper, with the aim of handing these resources back to the ‘Chilean people’ (UNCTAD III, [37]-[38]). Although Allende was a Marxist, the ‘people’ he claimed to represent was broader than just the working class. For Allende, overcoming the evils of capitalism and neo-imperialism required the unity of a more diverse set of groups. This was made clear in his final speech, delivered in 1973 while the military coup against him was taking place. In addition to the workers, Allende thanked ‘the peasant’, ‘the intellectual’, ‘the grandmother’ and ‘the mother’, as well the ‘patriotic professionals who continued working against the sedition’. For all these groups, Allende saw himself as ‘an interpreter of great yearnings for justice’ (Final Speech).

Allende’s discourse and practices resemble a way of ‘doing politics’ that Argentine theorist Ernesto Laclau and Belgian theorist Chantal Mouffe understand as ‘left populism’. In his book, On Populist Reason, Laclau argues that populism is a discursive strategy that constructs a political frontier dividing society into two camps: ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. For Laclau, this frontier comes about through the building of a ‘chain of equivalence’, whereby a series of unmet democratic demands come to appear linked or connected. In her book, For a Left Populism, Mouffe builds on Laclau’s theory of populism to argue in favour of left-wing populism. For Mouffe, while both left and right populism ‘aim to federate unsatisfied demands’, their ‘difference lies in the composition of the “we”’ (p 44). Right-wing populism tends to construct ‘the people’ in narrow and exclusionary terms, whereas left-wing populism tends to rely on an inclusive idea of ‘the people’. In Allende’s case, he worked to connect a wide range of demands, including yearnings for democracy, economic redistribution and national self-determination, through an inclusive notion of ‘the people’ that spanned workers, peasants, intellectuals, parents and professionals. This notion of ‘the people’ was defined against an ‘elite’ that comprised fascist, capitalist and neo-imperialist forces – all of which posed a very real threat to both the Government and ordinary people in Allende’s Chile.

At the same time, Allende was not hostile to international law or opposed to international institutions in the way some more contemporary modes of politics described as ‘populist’ have been (e.g., Jean-Marie and Marine Le Pen, Donald Trump, Viktor Orban, Jair Bolsonaro, or Giorgia Meloni). While Allende was critical of the way dominant understandings of international law had been used to support economic imperialism, his response was to put forward an alternative (or rival) international law.

Involving the Chilean people in the ‘battle for international law’

Allende’s alternative approach to international law, and the way it connected with his populist politics, can be seen in his decision to host the third United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in Santiago, Chile in 1972. This decision was significant for multiple reasons. First, UNCTAD III took place against the backdrop of Chile’s dispute with foreign corporations over the nationalisation of its copper, allowing Allende to stand defiant in the face of mounting pressure from states in the North. Second, the event was part of the Third World’s broader struggle for a more egalitarian economic system, which later took the form of the New International Economic Order (NIEO). In this regard, hosting it in the Third World was important. Third, and most significantly from the perspective of this post, hosting UNCTAD III in Santiago presented a way for Allende to bring international law to the Chilean people.

In the lead up to the official events, for example, Allende penned a letter[1] to the Chilean workers involved in the construction of the UNCTAD III buildings in Santiago. In this letter, he thanked the workers for ‘giving the best of [them]selves to erect the monumental work of the UNCTAD III buildings where one of the most important international battles [torneos] will take place’ and ‘nations will fight … to bring an end to the arbitrary structure of the international trade and financial system’. Later, during the official proceedings of UNCTAD III, Allende again brought up the Chilean people’s efforts, stating:

The passionate fervour that an entire people has put into the construction of this building is a symbol of the passionate fervour with which Chile desires to contribute to the construction of a new humanity, so that in this and in the other continents, hardship, poverty and fear may cease to be (at [106]).

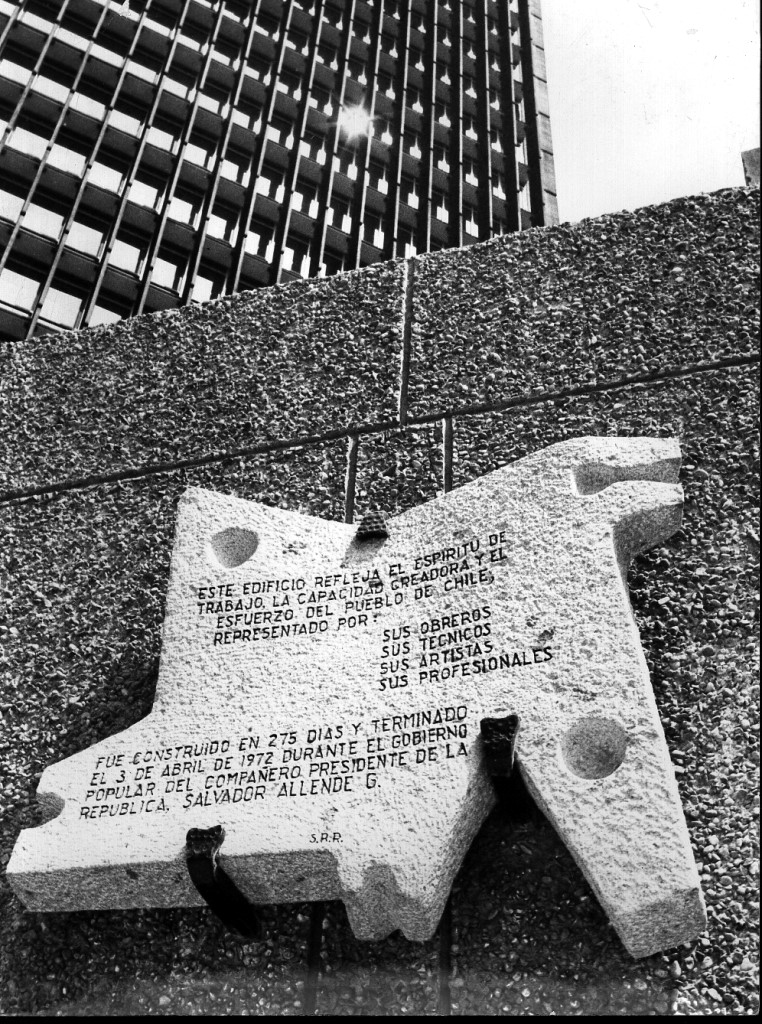

A plaque was also fixed to the building of UNCTAD III, which said ‘[t]his building reflects the spirit of work, the creative capacity and effort of the people of Chile, represented by: their workers, their technicians, their artists, their professionals’.

UNCTAD III stone plaque made by artist Samuel Román. Digital image courtesy of Miguel Lawner and Archivo Digital GAM (Santiago, Chile). Reproduced with permission.

In this letter, speech and plaque, we see Allende presented the Chilean people’s material contribution to the building of UNCTAD III as a contribution to the larger South-North ‘battle’ for international law that was taking place at that time. In drawing this connection, Allende suggested that it was not only lawyers, diplomats and heads of state who could participate in the making of international law, but also everyday people, from workers to artists to professionals.

‘Solidarity’ as an organising principle of international law and politics

In addition to involving the Chilean people in the Third World’s international legal battle(s), Allende was firmly committed to fostering forms of international solidarity that did not sacrifice the local at the altar of the international. As can be appreciated in his numerous speeches and letters, Allende was able to connect the particularities of the Chilean people’s struggle against structural inequality and resource extraction at the hands of foreign corporations with the shared history of colonisation and capitalism of the peoples of the Third World. This prompted Allende to consistently advance the idea of ‘solidarity’ as an aspirational principle of an alternative international ethos, which was both socialist and ‘South-facing’. Tellingly, the Cold War context in which Allende developed most of his political career did not stop him from fostering alliances (even friendships) with leaders of states in the Third World and Communist Bloc, both before and during his presidency. For instance, Allende visited the Soviet Union, and developed relationships with Third World leaders, such as Che Guevara, Cuba’s Fidel Castro, Brazil’s João Goulart, and Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh. Allende also sought to construct regional alliances by proposing the creation of a ‘Latin American Solidarity Organisation’ at the 1966 Tricontinental Conference in Cuba and offering strong support for the Andean Pact in 1969.

The notion of solidarity also underpinned Allende’s approach to international law and, in particular, the Third World’s legal struggle for a NIEO. In his capacity as President of Chile at UNCTAD III, for example, Allende used his opening address to call for an international economic law based around the principle of ‘solidarity’. In this speech, Allende stated that although ‘the world as it is, with all its injustice towards the underdeveloped countries, cannot be changed overnight’ [95], it was possible to use the Conference to begin laying ‘the foundations for a solidary economy on a world scale’ [98] [emphasis added]. According to Allende, this would involve creating an international economic system based on principles of peace and cooperation, in which ‘we peoples of the third world gain recognition for our rights through the restructuring of international trade and the establishment of relations that are fair to each and all’ [97]. Measures to achieve this vision included global disarmament, a reeling in of corporate power, and a transfer of issues relating to trade and development from the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which had ‘always been essentially concerned with the interests of the powerful countries’ [73], to the United Nations. For Allende, altering the rules of the global economy in this way would represent ‘a new form of human co-existence, founded at last on solidarity, after the long-drawn-out history of oppression through which we have lived and are still living’ [98].

A vision of international solidarity centred around the ‘peoples’ of the world

As in his domestic politics, Allende embraced a people-oriented discourse in his calls for solidarity in international law and politics. However, unlike in the domestic context, in which he regularly referred to a singular Chilean ‘people’, Allende’s internationalism was based around the idea of a plural but collective ‘peoples’. This can be seen in his speech to the UN General Assembly in 1972, in which Allende reminded the audience that it was ‘the peoples, all the peoples south of the Rio Bravo, that stand up to shout, “Enough – no more dependence”’, and stressed that ‘Chile is completely in solidarity with the rest of Latin America, without exception.’ For Allende, the struggle of the Chilean ‘people’ was interlinked with that of the ‘peoples’ of Latin America and the rest of the Third World. On the night that Allende became president-elect in 1970, for example, he addressed Chileans from the headquarters of the Federation of Students of the University of Chile (FECH in Spanish). According to one of Allende’s biographers, ‘[w]hile in the elite neighbourhood of Santiago a deafening silence reigned[,] … thousands and thousands of Chileans celebrated on the streets the historic victory of Allende and Popular Unity’ (Amorós, 2013, 276). From the balcony of FECH, Allende declared that his election, which ‘was not the struggle of one man, but the struggle of a people’, was a ‘victory which resound[ed] beyond the borders of this homeland’. For with its newfound economic independence, ‘Chile open[ed] a path which other peoples of America and the world, [would] be able to follow’ [emphasis added].

The legacy of Allende’s vision of international solidarity

Looking back today, with all we know about the fall of the Allende Government and the demise of the NIEO, it is easy to see only tragedy in Allende’s words on the balcony of FECH. But Allende’s solidarity with the peoples of the world was not expressed in vain. During his lifetime, Allende’s people-centred vision of international law and politics prompted artists and workers from all around the world to express solidarity back to Chile. As Allende told the UN General Assembly in 1972:

[W]e have been deeply moved by the solidarity of the world’s working class, expressed by its great trade union central organizations and demonstrated in actions of great significance, such as the refusal of port workers of Le Havre and Rotterdam to unload copper from Chile, for which payment had been arbitrarily and unfairly embargoed.

What is more, after the 1973 coup and Allende’s subsequent death, many around the world continued to express solidarity with Allende’s fallen Government, from ‘Third world queer feminist solidarity’ movements in the US, which mourned the struggle over Chile’s copper through poetry , to Third World governments as far away as Algeria, which maintained Allende’s ambassador as the ‘sole legitimate and legal representative of the Chilean nation’ for several years after the military junta had seised power (Palieraki, 2020, 292).

As time went on, and neoliberal thinking took hold in Western states and international institutions, human rights (sometimes described as neoliberalism’s ‘fellow travellers’) came to dominate narratives of Chile’s 1973 coup. Rather than an instance of neo-imperialism or capitalist counterrevolution, Allende’s overthrow and the dictatorship that followed began to be presented as mere ‘human rights violations’. With this reframing, expressions of international solidarity with the people of Chile and the fallen Allende Government were both reinterpreted as, and funnelled into, a depoliticised global human rights movement, which eschewed the economic elements of the story and focused on instances of individual suffering. Yet, as we have shown in this blogpost, Allende’s international law of solidarity was one that refused the international legal separation of the political and the economic, whether it be through his recognition of the labour that goes into the materiality of international law, and in particular its buildings, or his calls for changes to international trade law to create ‘a solidary economy on a world scale’. It was also one that centred the collective wellbeing of both the ‘people’ of Chile and the ‘peoples’ of the world.

This vision of solidarity, with its emphasis on collectivity and economic justice, is gradually being recovered. This can be seen in the return of forms of left-wing populism during the Latin American pink tide of the 2000s, the creation of new radical regional alliances, such as the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America in 2004, and the sound of nueva cancion during the anti-inequality protests in Chile in 2019. In this way, the story of hope associated with Allende’s people-oriented internationalism has not finished yet.

Put differently, ¡El pueblo unido jamás será vencido!

[1] There is no online link available to this document. The letter is reproduced for the first time in Mario Amorós, Allende: La Biografía (Ediciones B), 636. Translation by authors of blogpost.

Dr Claerwen O’Hara is a lecturer at La Trobe Law School. Dr Valeria Vázquez Guevara is a Global Academic Fellow at the University of Hong Kong’s Faculty of Law. Claerwen and Valeria are currently working on a joint project focused on international law, populism and alternative internationalisms.