The Alibis of History, or How (not) to Do Things

with Inter-temporality

By Ntina Tzouvala*

Published on 8 February 2023

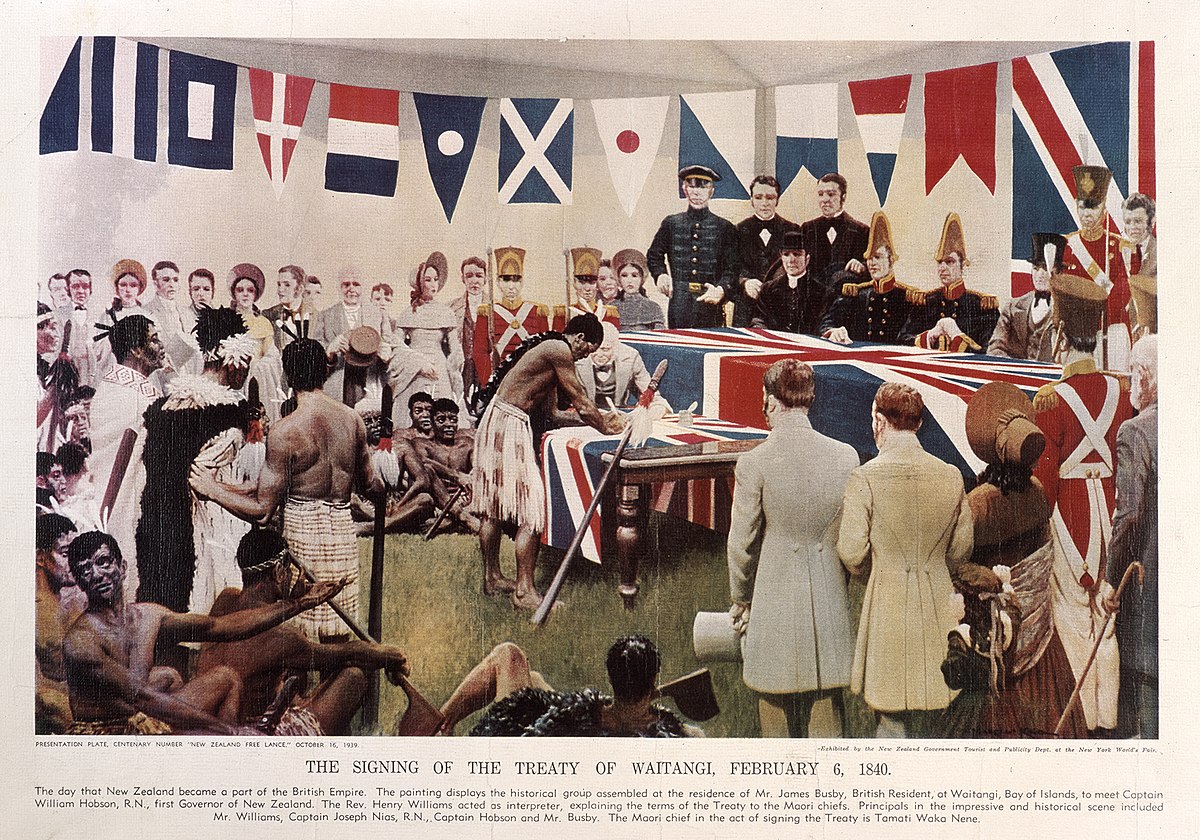

Photo Credit Reconstruction of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, Marcus King, Archives New Zealand

Efforts to confront the imperialist, colonial and racist foundations of contemporary wealth and prosperity in the capitalist West are often resisted by pleas not to judge historical practices against contemporary moral standards. This (dubious) argument also finds juridical expression in the international legal rules concerning inter-temporality. In a nutshell, the (il)legality of an act or an omission should be judged against the rules of international law that applied at the time that this act/omission took place and subsequent legal change does not affect this judgement. This is a rule with long historical pedigree going back to The Island of Palmas arbitration, a case concerning the rules applicable to the colonisation of inhabited lands by Western powers.

Discussions about inter-temporality have been revived in international law by ongoing efforts of different peoples to obtain reparations for historical and ongoing harms, including colonial atrocities but also climate change, and by the choice of these groups to demand these reparations not only as a matter of moral or political but also in terms of legal justice. Inter-temporality has been invoked by rich, Western states as a shield against such efforts. The argument is simple: at the time when, say, the genocide against the Herero and Nama people took place or when the vast majority of emissions were released into the atmosphere leading to climate change neither acts were unlawful under international (or domestic) law. As a result, the rules of state responsibility are not engaged (see also Articles 13 and 14 of ARSIWA) and no compensation or other form of reparation is owed, as a matter of law.

The practical and legal consequences of this position are considerable. For example, as Julia Dehm has shown, in international climate law developed states have been very careful to frame differential responsibilities as an expression of different state capacity, and not as a legal consequence of their disproportionate contribution to the phenomenon. Similarly, Germany agreed to make payments to Namibia in light of its genocide against the Nama and Herero people, but stressed that these payments would be developmental aid, and not reparations. It is actually this latter example that triggered my thoughts in this post. As Karina Theurer noted over at Voelkerrechts blog, this agreement between Germany and Namibia is now being challenged in front of Namibian courts. Theurer does a great job in summarising the grounds for this legal challenge and in explaining that it is Namibian public law, rather than international law, that is at the core of this legal case. At the same time, she stresses that the applicant also invoked domestic public law to challenge the Namibian government’s acceptance of the inter-temporality rule as part of the same agreement. The applicant, Theurer and others stress that this acceptance means giving contemporary legal significance to the racist distinction between the ‘savage’ and the ‘civilised’ and, therefore, to perpetuate the normative consequences of this distinction. I wholeheartedly agree with this assessment and I have a lot to say about the brutality and inequality inherent in the ‘standard of civilisation’. At the same time, my concerns about the rule of inter-temporality go beyond (or rather start before) those of Theurer and other critics. I believe that inter-temporality works in practice like a magic trick, as the magician directs our attention away from where the action is so that they execute their trick in front of our own eyes without us realising.

Allow me to explain using the example of Germany’s arguments in regards to the Nama and Herero genocide. Germany’s official position has been that ‘genocide’ was not an international crime at the time when it mounted its extermination campaign (1904-1908) and therefore it may use the term ‘genocide’ in the historical or moral sense to describe its brutal actions, but this does not imply any legal obligations. Prof. Stefan Talmon has also argued that: ‘Even allegations of genocide must thus be assessed against the yardstick that was applicable at the time when these acts occurred or were carried out. In 1904-1908, however, genocide did not yet exist as a concept either in treaty law or in customary international law. In addition, international law did not know of international law obligations of a State vis-à-vis its own citizens or the local inhabitants of its colonies.’

Can you see the trick? Both the government and Talmon slide from the debatable but plausible position that the prohibition genocide as such was not a rule of international law in 1904-1908 to the wildly implausible position that international law posed no limits to the treatment of colonial subjects. This is because even the most adamant defenders of the ‘standard of civilisation’ during the 19th and early 20th centuries acknowledged that some legal obligations were owed to the ‘uncivilised’, normally the ‘obligations of humanity’. It was exceedingly rare for academic or state lawyers to argue in the abstract that local populations could be fully exterminated or treated with wanton cruelty by their colonisers, even if in practice lawyers tended to tolerate or even excuse such actions. However, to recall the Nicaragua case, these excuses confirmed that these lawyers conceded the existence some kind of prohibitive rule in the first place. This prohibitive rule was exceedingly thin and its nominal acceptance did not do much to help those encountering imperial violence. Even the argument that ‘savages’ only enjoyed the ‘rights of humanity’ but not political rights under international law is difficult to sustain in light of state practice at the same time. Both in settler and in other colonies imperial powers frequently entered into treaties with Indigenous peoples. Undeniably, the validity of these treaties was not unanimously accepted at the time, but it was not unanimously rejected either. This extensive practice of treaty-making puts significant pressure to the idea that Indigenous peoples did not enjoy some degree of legal personality under international law, a personality that arguably came with some rights and duties.

All this is not to whitewash the ‘standard of civilisation’. To say that Indigenous peoples enjoyed the minimum right not to be slaughtered in large numbers and enough political rights to sign away their sovereignty and resources is not exactly complimentary toward international law of the time. However, to present an image of international law as demanding nothing from colonial powers has less to do with applying the rule of inter-temporality or respecting the alterity of the past and more with lawyerly work right here and right now. This work involves selecting the most flagrantly racist amongst past international legal opinions. In addition, it necessitates that we ignore scholars, humanitarians and government officials who—despite their severe limitations—raised questions at the time about the legality of how colonial governance and war were conducted. Finally, it demands that we erase entirely from the record the legal opinions of the colonised, who became very quickly fluent in the language of Eurocentric international law. All three moves are essential in order to present the resultant distortions as the rules in force at the time. Of course, this manipulation of past rules is not unique to the work of the respondents’ lawyers. The applicants’ lawyers also engage in similarly creative work, which is often the source of tensions and dilemmas for politically sympathetic historians who might be called to act as expert witnesses in front of courts. In that regard, both sides confirm Orford’s observation that the past plays a distinctive role in legal argumentation insofar as it is constantly retrieved to ground and rationalise present obligation (or lack thereof).

However, there is something distinct about the role of governmental or corporate lawyers when they argue that no legal obligations to make reparations exist today and they do so by invoking a combination of the rule of inter-temporality and the regrettably racist state of the law in the past. To argue as a lawyer in 2023 that no obligations were owed to ‘uncivilised’ peoples in 1904 is to actively and consciously make ‘the standard of civilisation’ part of current legal practice. This move involves remaking the ‘standard of civilisation’ and to do so in the image of its most extremist defenders. This is, indeed, the objection against invocations of the ‘standards of the past’: more often than not. These invocations ignore dissenting voices both from subordinated peoples but also from within dominant groups, voices that show that ‘the standards of the time’ were as contested as those of our time and arguments about fidelity to the past conceal political choices made in the present. This objection is especially relevant for international law, as this selective engagement with the past has both discursive and direct material consequences since it remakes the law to fit the desire of the powerful in the present not to compensate and it forecloses a legal redistribution of resources. Of course, this foreclosure is not definite, but it deprives those advocating for change from one important tool.

Looking closer to hegemonic arguments about the past state of the law is anything but a silver bullet. Even those lawyers who protested the most brutal aspects of colonialism often did so from within the logic of the standard of civilisation, a standard that relied on the gradation of humanity along rigid racial lines. Such a legal system is unlikely to deliver justice in the present. In addition, disaggregating the acts of the genocide against the Nama and Herero people and proclaiming some but not all them illegal at the time has the distinct disadvantage of not capturing the harm inflicting in its horrific totality. This is not a satisfying outcome. However, I maintain that we ought not to throw the towel too easily when it comes to the past of international law. If nothing else, we ought to make practicing lawyers keenly aware of the fact that it is their choices in the present that keep the ‘standard of civilisation’ alive and that they cannot place this burden on the feet of history.

* Ntina Tzouvala is a Associate Professor at the ANU College of Law)