Symposium: High Politics at the International Court of Justice

The Power of the World Court Unleashed:

The Chagos Archipelago Advisory Opinion and Decolonisation

By Trung Nguyen

Published on 21 October 2024

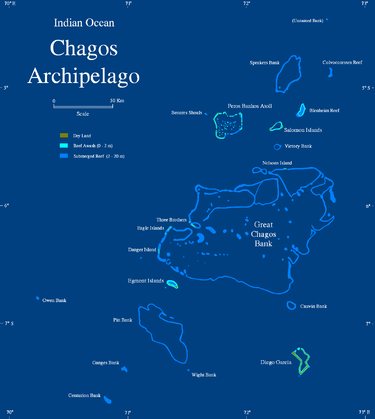

British colonialism marked a dark page in humankind’s history and it still haunts us today like the ghost of Hamlet’s father. The story of the Chagos Archipelago is emblematic of that era of imperialism. The native population of the Archipelago, the Chagossians, were forced to leave their homeland and never to return after the United Kingdom (UK) detached their islands from Mauritius’ territory with the 1965 Lancaster House Agreement to make way for an American military and security base in Diego Garcia.

In 2017, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 71/292 to request the International Court of Justice (ICJ or “the Court”) to render an advisory opinion on (i) whether the decolonisation of Mauritius was lawfully completed when it gained independence from the UK in 1968, following the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius and (ii) the consequences arising under international law from the UK’s continued administration of the archipelago.

This blog post will explore the contours of the ICJ’s advisory function by looking at the Chagos Advisory Opinion case (the “Advisory Opinion” or the “Opinion”). It will not provide a detailed analysis of the substantive parts of the Opinion, which has been done elsewhere (See here). Rather, it will argue that, in this case, the ICJ stepped out of its usual restrained and prudent stance to offer bold pronouncements in high-politic cases concerning issues that are of utmost importance to the United Nations’ mandate, namely decolonisation. My piece will emphasise the implications of the Advisory Opinion in subsequent developments, notably concerning the rise of politically contentious cases pending before the Court.

Political questions and politically sensitive questions

At the outset, there is a distinction to be made between “political questions” and “politically sensitive questions.” A political question refers to the non-legal aspect of a certain dispute that should be settled by the stakeholders in a negotiation room rather than by a court of law. To the contrary, a politically sensitive question refers to a legal dispute that happens to be controversial, the legal determination of which is set to have political repercussions.

Regarding the latter, in the ICJ’s viewpoint, the fact that the case might be highly political cannot, by itself, prevent the Court from discharging its judicial tasks and dealing with it on legal grounds (Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, para. 41; Declaration of Independence of Kosovo, para. 217). Put differently, the ICJ will not decline to rule on a case simply because the issue at stake is highly sensitive.

When it comes to the former, in contrast, the ICJ has shown that it is not completely insensitive to the political machinery operating outside of the courtroom. The Court has been found to be prudent and often uses a range of “issue avoidance” techniques to keep away from pronouncing on the political aspects of a legal dispute. For example, in the Nuclear Weapon Advisory Opinion, a politically sensitive case that concerned the permissibility of the use of nuclear weapons under international law, the ICJ decided that it did not have “sufficient elements” under the existing law to answer the question posed by the UNGA (para. 96) (See also Nuclear Disarmament Case). In other instances, the Court reformulated the original question asked by the UN bodies into what it believed was “the true legal question” to avoid the politically sensitive aspect of the case (See Interpretation of an Agreement between WHO and Egypt Advisory Opinion, paras. 28, 35; South West Africa Advisory Opinion, p. 25; Kosovo Advisory Opinion, para. 56). At times, the ICJ has been criticized by some of its former judges, such as Pieter Kooijmans, for being “unduly restrained” in addressing politically sensitive questions and, thus, undermining the rationale for brining issues before the Court in the first place.

Nevertheless, and as the remainder of this post will show, the Chagos Advisory Opinion is a peculiar case where the ICJ has exercised its authority as a principal judicial organ of the UN to pronounce on a high-politic case, instead of using issue avoidance tactics as it did in some past proceedings.

The Chagos Advisory Opinion

The events that preceded the Chagos Advisory Opinion suggested that it was more than a simple legal question addressed to the ICJ. The advisory opinion was initiated in the context of a long series of dispute. In 2010, Mauritius launched a case over the UK’s establishment of a marine protected area around the Chagos Archipelago. In that case, the Annex VII UNCLOS Arbitral Tribunal found that it lacked jurisdiction to determine whether the UK was a “coastal state” of the Chagos Archipelago. In addition, in 2012, a group of Chagossians sought to bring the UK before the European Court of Human Rights (“ECtHR”) claiming that the UK’s ordinance preventing them from returning to their homeland violated rights protected by the European Convention on Human Rights. The case was declared inadmissible by the ECtHR which found that the case had been definitively settled in the UK courts and the Chagossians had waived the right to bring any further claims before them. Thus, it has been argued that the Chagos Advisory Opinion served as a continuance of Mauritius’ efforts to affirm and reclaim its sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago using legal means. In their written statements, the UK, US and Australia argued that the issue at hand was by nature a bilateral territorial dispute between Mauritius and the UK concerning sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago and the ICJ should not entertain the UNGA’s request because the UK did not consent to dispute settlement.

In this case, the ICJ was caught between decolonisation and self-determination issues on the one hand –of vital importance to many Third World countries that make up a majority of the UN membership- and the principle of state’s consent to judicial settlement as well as the so-called security interests of the Western bloc, as advocated by two permanent members of the Security Council, on the other. In rendering the Opinion, the Court decisively moved away from its earlier prudent approach and took a bold stance to address issues of direct interest to the Global South.

The ICJ took into consideration the contentious aspects of the advisory proceeding, such as the argument that the true nature of the case was a bilateral dispute of sovereignty, and contemplated whether the case circumvented requirement of consent to judicial dispute settlement, but did not find either argument persuasive. The Court emphasised the importance of bringing colonialism to an end, which is an essential mandate of the international community and the UN system (para. 87). In the Court’s view, the posed questions “are located in the broader frame of reference of decolonisation, including the General Assembly’s role therein, from which those issues are inseparable” (para. 88). As such, it decided that there “are no compelling reasons for it to decline to give the opinion requested by the General Assembly” (para. 91).

In the intervention stage, several countries asked the ICJ to reformulate the questions posed by the General Assembly or to interpret them restrictively and limit the advisory opinion to the general function of the UN concerning decolonisation and exclude all issues concerning states’ obligations. However, the Court, while recalling that it can do so, decided that “there is no need for it to reformulate the questions submitted to it” in these instances (para. 136). In other words, the Court felt that it was unnecessary to avoid the politically sensitive aspect of the posed questions.

Against the idea of Judge Donoghue, who thought that the ICJ “should have exercised its discretion to decline” to give the Advisory Opinion as it might entail a decision on the UK’s obligation without its consent to judicial dispute settlement, the Court went ahead with the case. It pronounced that the process of decolonisation of Mauritius was not lawfully completed and was not conducted in a manner consistent with the right of peoples to self-determination (paras. 174, 177). This statement meant that the UK administration of Chagos is illegal under international law.

Regarding the second question concerning the legal consequences of Mauritius’ ongoing partition, the ICJ stated that the UK’s continued administration of Chagos constitutes a wrongful act that triggers the state’s international responsibility (para. 177). Notably, it added that “the United Kingdom is under an obligation to bring an end to its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible, thereby enabling Mauritius to complete the decolonisation of its territory in a manner consistent with the right of peoples to self-determination” (para. 178). The Court added that since the right to self-determination is an obligation of erga omnes, all UN Member States must co-operate with the United Nations to complete the decolonisation of Mauritius (para. 180).

Broader Implications

The Chagos Advisory Opinion was not the first time the Court had been asked to deal with decolonisation, self-determination and territorial integrity in an advisory capacity (See Western Sahara, Namibia, The Wall, and Kosovo). However, what set it apart from these past decisions is the Court’s willingness to openly and unequivocally condemn the illegal actions of a European colonial power.

Subsequent developments show that the ICJ’s stance was not an isolated occurrence but is based on a much more fundamental movement within the international community against the systematic displacement and exploitation of former colonies. This is evident in the sweeping 116 votes to 6, despite the UK lobbying effort, in the UNGA’s Resolution endorsing the Advisory Opinion and demanding that the UK withdraw unconditionally from Chagos within six months. The result of this Advisory Opinion also paved the way for the Special Chamber in Mauritius v. Maldives, a maritime delimitation case, to confirm its jurisdiction based on the premise that Mauritius’ sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago “can be inferred from the ICJ’s determinations” (para. 246). This anti-dispossession legal position of the ICJ also found its way into the latest Occupied Palestinian Territory Advisory Opinion of the Court. In citing extensively its earlier Opinion in Chagos, the ICJ condemned Israel’s illegal presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (para. 267) and stated that Israel’s “security concerns” cannot override the principle of non-acquisition of territory by force or justify its (mis)treatment of the Palestinians (paras. 205, 254; See also Declaration of Judge Tladi, paras. 42ff). Notably, the ICJ identified the right to self-determination in cases of foreign occupation as constituting a peremptory norm of international law – jus cogens – (para. 233). This is a ground-breaking development based on the Court’s earlier finding in Chagos that the right to self-determination is a “fundamental human right” and “has a broad scope of application” (Chagos Advisory Opinion, para. 144. See also Declaration of Judge Xue, para. 4; Separate Opinion of Judge Cleveland, para. 34 and Declaration of Judge Tladi, para. 19 in Occupied Palestinian Territory Advisory Opinion).

In a nutshell, the Chagos Advisory Opinion is a decision of enduring importance, not only for Mauritius but also for the development of the contemporary international legal system and order. Just as the Namibia and Western Sahara advisory opinions marked a progressive step toward decolonisation and the Wall and Kosovo opinions reflected the importance of the principle of self-determination and territorial integrity at the turn of the millennium, the Chagos Advisory Opinion can be seen as a pivotal moment of an era where formerly dominant Western powers must come to terms with their diminishing power to shape the international system. The road for Mauritius to reclaim the Chagos Archipelago might be long and winding (See here and here) but it marks humankind’s irreversible march toward the end of colonialism. In this process, the ICJ has undoubtedly played a key part as a forum for adjudicating broad legal and political questions in light of the World Court’s role as a principal judicial organ of the UN.