Symposium Introductory Blog

Use of force, territorial integrity, and world order: continuing the debate

by Dr Ntina Tzouvala (ANU College of Law)

Published on 20 March 2023

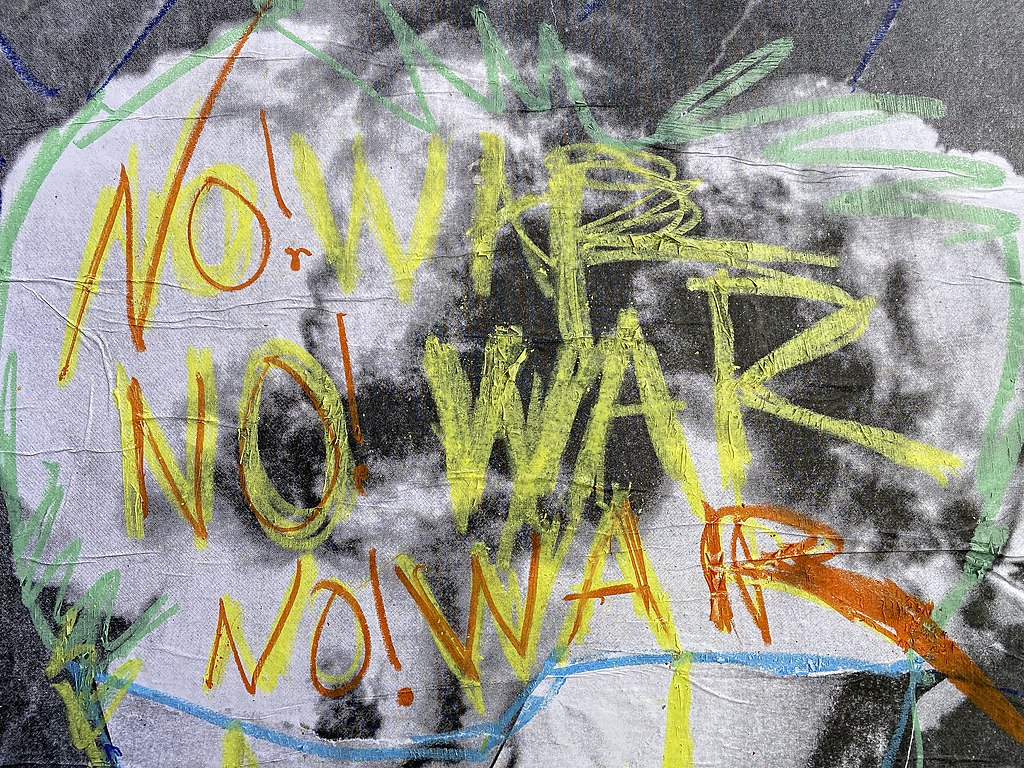

“NO WAR – piece of art in the streets Berlin” by Etienne Girardet. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Few international legal fields witness the intensity of debate, disagreement and feeling that jus ad bellum does. Linked to foundational ideas of sovereign prerogative, security, international order and (anti)imperialism, the international law of the use of force has been highly contested and highly coveted. The sheer number of times that Article 2 paragraph 4 of the United Nations (UN) Charter has been proclaimed dead speaks to the investment to its survival by both scholars and practitioners, even if this survival is especially valued when it binds one’s opponents rather than oneself and one’s allies.

The 2022 invasion of Ukraine by Russia is no different. A clear escalation of a conflict that has been ranging since 2014, the invasion has attracted almost unanimous condemnation by international lawyers in the West. Beyond the West, the situation is more complex. Some Global South states and lawyers have condemned the invasion in the strongest of terms observing that the destabilisation of norms such as the prohibition of the use of force and territorial integrity will be particularly harmful to postcolonial states. However, many postcolonial states have chosen to stay silent. Sometimes, this silence is due to varying degrees of support for Russia. In other instances, it reflects a reluctance to become involved in what they see as a geopolitical competition that does not concern them directly. In the realm of law, concerns about Western hypocrisy and double standards when it comes to prohibition of the use of force and territorial annexation are often invoked to justify this ambivalence by many Global South actors but also by dissenting voices within the West. At the same time, it is telling that even Russian allies have opted for silence over overt defence when it comes to the lawfulness of Russian actions: it seems almost impossible to reconcile Russia’s aggression with even the most minimalist understanding of the prohibition of the use of force.

This absence of organized defence of the invasion’s lawfulness—besides Russian lawyers and politicians—should not be confused with broader consensus on the meaning and place of the invasion within the international legal order as a whole. The purpose of this symposium is, then, to highlight one core disagreement and move the disciplinary conversation forward. In late 2022, Professors Ingrid (Wuerth) Brunk and Monika Hakimi curated an Agora dedicated to the international legal dimensions of the conflict for the American Journal of International Law (the contributions can be found here). Although the contributions dealt with a broad range of issues, the editorial note co-authored by (Wuerth) Brunk and Hakimi, focused heavily on jus ad bellum. Their main argument was that Russia’s open intention to alter international borders and the lack of limiting principle in its legal justifications render this instance of use of force singularly dangerous for the international (legal) order. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this turned out to be a controversial argument sparking extensive debate on social media and beyond.

The purpose of this symposium, then, is to make this debate more systematic and analytical than social media allows. For this purpose, CIL Dialogues has brought together four critical commentaries as well as a response by (Wuerth) Brunk and Hakimi. Our symposium opens with a piece by Professor Alejandro Chehtman, who reflects on whether it is justified to argue that Ukraine constitutes a unique challenge to the international (legal) order especially in comparison to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Chehtman’s piece decentres statist defences of the prohibition of the use of force and of territorial integrity in international law. Instead, he adopts a human-centred approach that focuses on the purpose of these rules, which he argues lies in the protection of humans from the suffering, destruction and death that comes with aggressive war. For Chehtman, taking this purpose seriously renders extremely doubtful whether the 2022 invasion of Ukraine has challenged the international legal order more profoundly than the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Chehtman’s piece is followed by a contribution by Professor Sâ Benjamin Traoré, who offers an insightful analysis of the relative apathy coming from some Global South states regarding the invasion. His argument relies on a close examination of states’ voting patterns in the UN General Assembly and, in particular, the practice of abstention by many postcolonial states. His argument is twofold: first, he highlights concerns about selectivity and double standards. Dissecting accusations of ‘whataboutism’, Traoré’s piece demonstrates that equal application of the law is a minimal prerequisite for a legitimate legal system and that, more practically, it is a major concern for a wide range of states that are active participants in this system. Secondly, he turns his critique toward inactive postcolonial states arguing that, ultimately, the weakening of the prohibition of the use of force and of territorial integrity will affect them negatively. For this reason, he states that if anything positive can emerge out of this terrible conjuncture is a practical reaffirmation of these rules as rules of universal application.

The third piece of this symposium was written by Ms Anastasiya Kotova together with the undersigned. Our contribution takes issue with the ‘exceptionalisation’ of territorial integrity in (Wuerth) Brunk’s and Hakimi’s original piece. We emphasize that Article 2 paragraph 4 is drafted in the broadest terms and that it protects not only territorial integrity but also political independence from violent imposition. Further, we posit that to ‘exceptionalize’ the former squares (consciously or not) with the modalities of US imperialism that has generally (although with crucial exceptions, especially in the Pacific) relied on targeted uses of force and political interference rather than territorial annexation. Even though we welcome the revival of international concern about aggression, we warn against gutting the protective scope of the prohibition by over-emphasizing territory over a comprehensive protection of political independence.

In the final critical contribution, Professor Ardi Imseis tests the argument that the invasion of Ukraine is unique because it aims at violently annexing territory against the ongoing attempts of Israel to annex the Golan Heights as well as the Occupied Palestinian Territories and of Morocco to annex Western Sahara. Imseis details both the long history of condemning these attempted annexations as unlawful under international law and the equally long practice of ignoring them by Israel and Morocco. Crucially, he also shows that many Western states that are now vocally concerned about aggression and territorial integrity have shown tolerance, if not outright complicity, towards these unlawful acts. In particular, he highlights that many decisions made under the Trump administration, including the recognition of Israel’s sovereignty over East Jerusalem and Morocco’s over Western Sahara, have not been reversed by the Biden administration in over two years in office, indicating a commitment that goes beyond purportedly ‘anomalous’ periods. Imseis concludes his account with a plea for universality when it comes to the core rules of international law.

Our symposium concludes with the response of (Wuerth) Brunk and Hakimi. Their contribution develops in three main parts. First, they clarify that their argument that Russia’s aggression poses a unique challenge to the international legal order does not involve a moral approval of this order or a claim that this order does not enable particular forms of imperialism. Secondly, they posit that Russia’s legal justifications are distinct insofar as they do not build upon prior international institutions’ decisions, but rely solely on the unilateral acts of one state to create legitimacy. Finally, (Wuerth) Brunk and Hakimi develop their argument that wars of territorial acquisition are destabilizing in unique ways. They revisit the extensive legal protections afforded to territorial integrity and state survival under international law and they place the prohibition of annexation at the core of the post-World War II international legal order. Indeed, they emphasize that contemporary practice confirms this intuition: the UN General Assembly resolution on the territorial integrity of Ukraine commanded the most widespread support amongst UN member states. Ultimately, (Wuerth) Brunk and Hakimi conclude their contribution with a call to reaffirm the core prohibition of annexation by force in Ukraine and beyond.