What Trump’s Intervention in Venezuela reveals about International Law

By Alexandra Hofer

Published on 29 January 2026

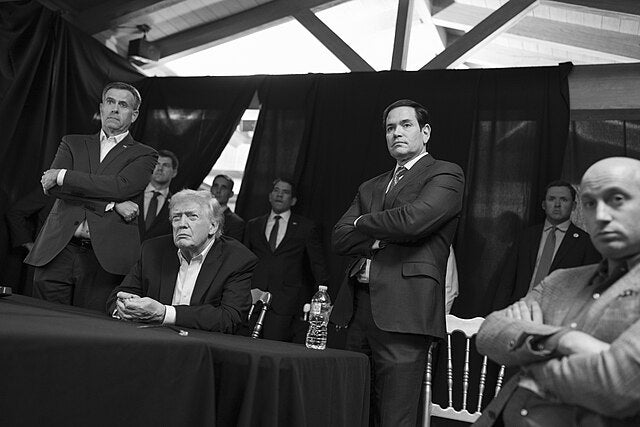

On 3 January 2026, the US used force against Venezuela to kidnap its head of state, Nicolas Maduro, and his wife, Cilia Flores. The intervention marks the cumulation of the US desire for regime change in Venezuela and for control over the country’s oil—goals that have been openly discussed by officials and representatives over the years. John Bolton transparently wrote about pursuing regime change in Venezuela during his time as national security advisor. Elliot Abrams, who was involved in the Iran-contra affair and then advised George W. Bush on the Middle East from 2002 to 2007, published an article in Foreign Affairs in November 2025 calling for the US to overthrow Maduro. Californian Representative Salazar spoke forcefully in favour of removing Maduro and making way for American companies to gain access to Venezuelan oil (CNN, 1 December 2025). Shortly after the intervention, Trump held a meeting on 9 January 2026 with the US’s biggest oil investors over operations in Venezuela, although some may be wary of entering an uncertain market. It has been noted that the US’s attack on Venezuela could thwart Chinese influence in Latin America, in line with the 2025 national security strategy that seeks to keep strategic competitors out of the Western hemisphere.

The intervention triggered a slew of commentaries on the relevance of international law (see here, here, here and here). During a UN Security Council meeting called for by South Africa (a non-permanent member), delegates ‘warned that Washington, D.C.’s actions threaten the very foundations upon which the multilateral world order was built; (though Argentina, Paraguay and Trinidad and Tobago expressed support for US intervention). Claiming that Maduro has no legitimacy to govern Venezuela, the US delegate made no effort to refer to the UN Charter, and justified the kidnapping as a ‘law enforcement operation’ intended to apprehend a wanted criminal for drug trafficking (see also here). While the kidnapping of a sitting head of state is unheard of, it is not the first time an international incident triggers doubts about international law’s relevance, and multiple US policies under President Trump have given rise to this question (see, for example, here and here). But there is something distinct this time around. In intervening in Venezuela, Donald Trump and his administration have not even played lip service to international law, particularly the UN Charter. When asked whether international law ever causes him to have restraint, Trump said that only his ‘own mind’ and his ‘own morality’ can stop him.

Some responses from third states have been rather tepid. Reactions from states who often portray themselves as defenders of international law are particularly striking. French President Macron’s initial statement made no reference to international law, welcoming instead a democratic transition in Venezuela. The Canadian government issued a statement hailing ‘the opportunity for freedom, democracy, peace, and prosperity for the Venezuelan people’. While it calls for respect of international law, it makes no concrete reference to the US’s use of force against Venezuela. EU High Representative Kallas, Australian PM Albanese and German Chancellor Merz made similar statements. British Prime Minister Keir Starmer came under fire for avoiding commenting on the matter, saying he needed to establish the facts first. This was supported by British Attorney General Richard Hermer who explained that it is normal for states to consider matters of statecraft before calling nations out for breaching international law. In other words, it is best not to condemn allies. Meanwhile, Spain, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Uruguay issued a joint statement explicitly condemning the US, describing its actions as ‘an extremely dangerous precedent for peace and regional security and endanger the civilian population’. Switzerland, Russia and China also vocally condemned the US for breaching international law, including the prohibition to use force.

As mentioned above, it is far from the first time that a powerful state undermines the sovereignty of another; history is replete with such examples, many of which involve the US. But these interventions have either been carried out covertly and therefore did not fall under scrutiny, or with some attempt to articulate a justification under the UN Charter, even if it was not always convincing. A well-known example is the 2003 US-UK invasion of Iraq. In this case, the intervening countries (in)famously claimed they were acting lawfully because Saddam Hussein’s failure to comply with UNSC Resolutions reactivated UNSC Resolution 687 that authorised the use of force against Iraq in 1991. In other words, they relied on a ten-year old authorisation to use force. The US also made vague references to preemptive self-defense (see generally here). These arguments were hardly convincing, and it is hard to maintain that the invasion was not an act of aggression, but at least there was some engagement with international law. Over twenty years later, the US foreign policy motives behind the invasion of Iraq remain unclear, but one can speculate that oil-related considerations played an important part. In the case of Venezuela, however, the US has provided justifications that, far from concealing, highlight its intention to gain control of Venezuela’s crude oil and its actions since leave little room for doubt.

In an attempt to make sense of what is happening, it is perhaps helpful to inquire what Trump’s actions reveal about the international system, and literature may assist us in interpreting them. In not bothering to pretend to care about international law and in openly talking about controlling Venezuela’s resources, Trump’s behaviour is reminiscent of The Fool. As a literary figure, the Fool does not abide by shared social norms (such as providing legal justifications for military interventions) and is, therefore, freer to speak the truth (‘we want to control access to Venezuela’s resources’), if only accidentally. This archetype helps us gain awareness by acting as a “potent truth-teller” who holds a mirror up “to the monarch and to all of us” (Gordon, 2017).

Trump has not bothered to invoke international law to justify the attack on Venezuela and does not even seem to think it is necessary. In doing so, he has revealed something disconcerting about the role of international law in international politics: it provides an alibi for states to carry out coercive measures and distract us from their genuine objectives. As long as interventions can be made to fit within the existing legal framework (even if it is stretched), international law unwittingly enables states to carry them out, while distracting other states and commentators with discussions on the interpretation of a UNSC resolution, whether self-defence is applicable, or whether a government has provided valid consent. International lawyers would probably feel better if Donald Trump adopted language they are comfortable with, leaving them to comment on whether self-defence can be invoked against ‘narco-terrorism’ (for example). Yet the intervention in Venezuela is too crude (no pun intended) to look the other way. This reveals the tension between the world as it should be according to international law’s expectations and the world as it is. In The Sentimental Life of International Law, Gerry Simpson addresses how international law as a system of ‘thought, method, speech, professional expectations’ shapes our worldview, ‘constraining how we think about the world and isolating us from how we think about it’. A strict adherence to the language of international law conceals the economic and geopolitical motives behind warfare (though this, of course, does not mean critical studies of international law are not possible, see here and here). True, these are often shrouded in secrecy. But if we consider the bigger picture within which interventions take place and ask critical questions, we may be able to glean some understanding of why events occur and to what extent international law enables or constrains them.

It should not come as a surprise that an American president is undermining, or even foregoing, the international legal system. The Trump administration’s total dismissal of international law is the logical cumulation of the US’s ‘cherry-pick’ approach to international norms. Following the invasion of Ukraine, the Biden administration touted the importance of the ‘rules-based international order’, but as Dugard points out, the term is hardly a synonym for international law. He writes:

the rules-based international order may be seen as the United States’ alternative to international law, an order that encapsulates international law as interpreted by the United States to accord with its national interests, ‘a chimera, meaning whatever the US and its followers want it to mean at any given time’. Premised on ‘the United States’ own willingness to ignore, evade or rewrite the rules whenever they seem inconvenient’, the [rules-based order] is seen to be broad, open to political manipulation and double standards. (references omitted)

We should also not lose sight of the fact that the US is not a party to a number of multilateral treaties (notably the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Rome Statute, the 1977 Protocols to the Geneva Conventions, and numerous human rights treaties), and that it has a track record of undermining the work of international organisations when this suits its interests (the sanctions imposed against the International Criminal Court are a telling example). Viewed in this way, Trump’s decision to withdraw the US from sixty-six international organisations is simply honest foreign policy.

US allies upheld this system by playing the role of subordinates who had something to gain from the system and provided the US with legitimacy; their response to the kidnapping of Nicolas Maduro and Cilia Flores only highlights their complicity. Hegemony is relational, it emerges from a ‘social contract’ between a dominant State and subordinates. The dominant State enjoys a position of authority because it provides order, but as soon as it fails to fulfil this role its legitimacy will likely be challenged (see generally Lake, 2011). This was candidly articulated by Canadian PM Carney at Davos:

For decades, countries like Canada prospered under what we called the rules-based international order. We joined its institutions, praised its principles, and benefited from its predictability. We could pursue values-based foreign policies under its protection.

We knew the story of the international rules-based order was partially false. That the strongest would exempt themselves when convenient. That trade rules were enforced asymmetrically. And that international law applied with varying rigour depending on the identity of the accused or the victim.

This fiction was useful, and American hegemony, in particular, helped provide public goods: open sea lanes, a stable financial system, collective security, and support for frameworks for resolving disputes. So […] We participated in the rituals. And largely avoided calling out the gaps between rhetoric and reality. This bargain no longer works.

It is telling that Carney’s speech was given after Trump made it clear that he is serious about annexing Greenland, a direct threat to Denmark. It is only when their security interests are at stake that Western leaders are inclined to voice concern over the consequences of Trump’s policies for the future of international law. It is also noticeable that his speech references Greenland and Ukraine, but omits Venezuela, Palestine, Sudan and other states that have been on the receiving end of interventions either carried out by or (indirectly) supported by the West in recent years.

The US intervention in Venezuela and Carney’s speech are part of a series of events that suggest power relations are being reshuffled and that we are heading into a multipolar world order. Within these shifting dynamics some may argue that international law is more important now than ever, but I argue that critical international law is more important now than ever. This means that in order to be truly meaningful, international law needs to be understood within its context—as a product of politics, power and interests—not separately from it. Only by not taking legal arguments and statements in favour of international law at face value and by holding leaders accountable will we spare ourselves from being fooled (again).